Your Planets

Portraits of the Planets

Aspects between Planets

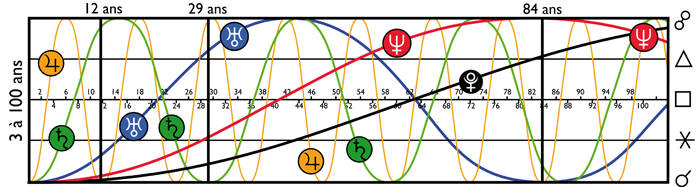

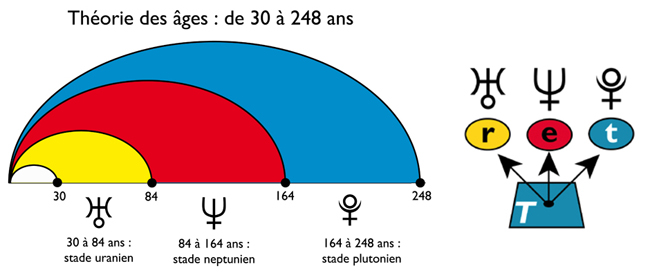

The planetary ages

The planetary families

Planets in Signs

The Planets in comics

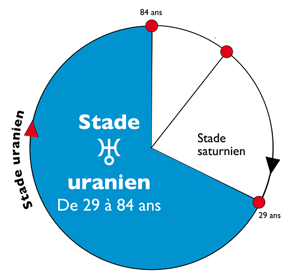

At thirty, childhood is already far away. In thirty years, the newborn has in principle become an autonomous, independent, responsible and self-confident adult. Why then evoke in this book the long period of thirty to eighty-four years? Because when the child who has become an adult escapes his parents to live his own life, he continues to grow, to learn, to change, but above all because the long stage governed by planet uranus is what parents experience while raising their children. The adult is not “final product”, he also learns, and yet it is striking to note how little psychologists have shown interest in the functioning of adults. It is therefore useful to inventory the various gains and losses that characterize this period, during which one successively becomes adult, middle-aged and finally old man.

If it seems relatively easy to observe the similarities of functioning in children of the same age group, it is apparently less obvious with regard to adults: during the quarantine, the definitive individual personality is in general established, hardly susceptible to major changes, and each seems to manifest at the highest point, even to the point of caricature at times, the specific nature of his character. The adults are so different from each other, so strongly individualized that we tend to consider each of them as a unique specimen.

And yet… Adults, however different they may be from each other, belong to the same age group, whose specific problems, vision of the world, prejudices, questions, sentimentality, type of intelligence, etc. During the long duration of the sidereal revolution of the planet Uranus, which governs the period of thirty to eighty-four years, our growth continues, even if it seems less evident, even if it is true that man has already behind him seven stages of learning and that one learns infinitely more things during his first thirty years than during those who remain to live. From thirty to eighty-four years, a major objective is essential: to affirm and fully accomplish one’s individuality, to bring together and coordinate the different facets of one’s personality to become fully oneself.

It is well known: around the age of 30, each of us lives with more or less intensity a period of transition during which we evaluate what we have already accomplished. We take stock of his failures and successes, satisfactions and dissatisfactions. Some thus radically call into question their professional choices or emotional and decide to reorient their lives according to new priorities, often telling themselves that they no longer have the right to make mistakes. The age of thirty, which sees the beginning of the Uranian stage, is a great turning point in life.

The idealism and the groping and anxious research of the adolescent must give way to the cold adult realism, the values integrated in the previous stage now tend towards efficiency. It is no longer a question of introspection: adults aged 30 to 40 are less and less inclined to reflect on themselves. He is primarily concerned with his career, his passion or his vocation, seeks to become a good performer in the branch he has chosen, conforming to the rules, worried about his advancement, ready to accept many aspects of the social system. We don’t play anymore. No time to waste: he works relentlessly to become a specialist in his field, launched into a frantic competition with his rivals who, like him, aim for positions of power and responsibility.

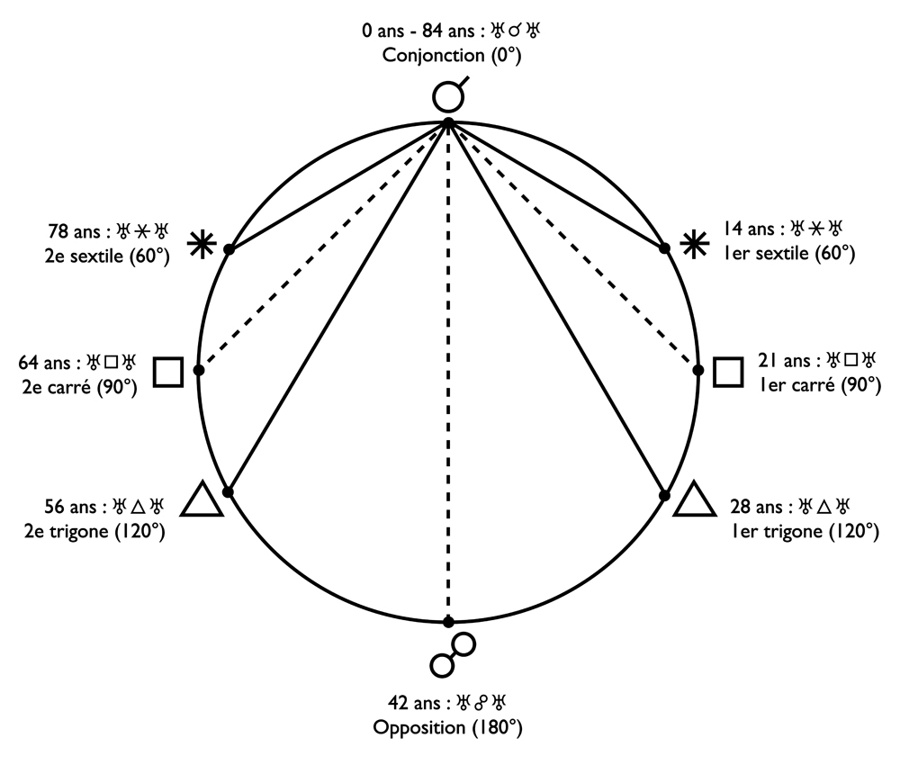

Chance and uncertainty are banished. You have to know what you want. The typical adult sets specific goals and cultivates high ambitions which he intends to achieve according to a precise timetable (at thirty, the deadline is often that of forty years, the approximate duration of the half-cycle of Uranus — 84 /2 = 42). He settles into a lifestyle he has chosen, founds a family, seeks stability and social and professional recognition. The adult is therefore a whole being stretched towards precise and ambitious goals that mobilize all his energy and hardly encourage introspection.

It programs its activities for the long term, chooses, elects, decides, decides. At the beginning of the stage, there is too much focus on individual success. Excessively inclined towards the process of individuation, the conquest of a skill, of a precise positioning in his socio-professional environment allowing him to emerge from the undifferentiated mass, he stubbornly seeks to extricate himself from doubt, from uncertain, randomness; abandoning his present situation, inhibiting his affects, he intends to impose his personal synthesis, his style, his own vision of what the order of the world should be.

While at the previous stage, the adolescent did not hesitate to put himself at odds with the dominant social consensus, the adult seems to operate as a return to the conformity of the Jupiterian stage (two to twelve years). This resemblance should not, however, mislead us: if the acceptance of consensus is a necessary adaptation in the Jupiterian child (“So is the social universe, and I conform to what it expects of me”), it is more of a deliberate choice in adults: “Since all things considered society is like this and I can’t spend my time challenging it like a retarded teenager, I have to deal with it in order to fulfill my role and conquer my place.” Thus the dynamic of conforming social insertion is above all for the adult the expression of a hyperacute lucidity—which one could possibly qualify as cynical (in the etymological sense, as it is true that for the cynical Greek philosophers, the happiness is obtained by a solitary exaltation of the will).

Adults want to be efficient, lucid, efficient, whatever their sector of activity. Chance, gambling, dreams, fantasy are deliberately excluded from his universe, gratuitous curiosities are banished, and the fundamental questions posed by the adolescent are postponed until later: all this harms the effectiveness of the action, the smooth running of the program, the sovereign exercise of will. A desire focused on a single goal: to succeed in finding its individual place in the collective concert, to make the values that inhabit it socially effective. He feels mature, responsible, able, if he is original, to impose his personal views… or less personal when he is content to be the loudspeaker, to become the conformist and convinced spokesperson of his generation.

The adult leaves the tests and the adolescent interrogations for well-defined objectives. In the best of cases, the clear and distinct idea that he has of his possibilities of development allows him to formulate his principles and his goals with maximum precision. The multiplicity of questions that assailed the teenager find answers that would be definitive, which are intended to structure his behavior that he wants to be efficient, competitive or more simply competent. Ideally, the adult is “one who knows”, the one who has a capital of experience from which he can extract the “marrow noun” in terms of knowledge, the one who doubts nothing, the one who imposes his vision of the world and his knowledge on ignorant babies, eager children and doubtful adolescents.

Adult intellectual functioning is characterized by a preponderance of synthetic intelligence. He no longer seeks hypothetical knowledge like the adolescent, he gathers, organizes and crystallizes all of his knowledge into a sharp beam. The adult mental universe is not very flexible, but knows how to fully exploit a capital of knowledge. The stated truths must be clear, clear-cut, compelling, unambiguous. Concentrated, polarized, specialized thought knows what it wants and where it is going, programs activities without hesitation: it is above all an instrument of decision-making.

Of course, it can be difficult for such a thought to remain fluid, to change smoothly, to decenter itself. Adults are often too sure of the validity of their assertions, of their certainties, and generally do not support contestation, the questioning of their vision of the world. Thus he clings firmly and sometimes exaggeratedly to the principles, ideals and concepts which he considers universal, as if he fears that chaos and disorder will set in if he does not maintain a concentrated attention in this area, relentless vigilance. After all, it is the adult man who is in charge of society, who says and makes the laws, imposes his authority and his values, often even allowing himself to abuse power.

It is often around the age of forty that the adult decides to go it alone, to show his personal card, to deploy the great game of conquering independence. He can no longer bear to be oppressed, restrained or dominated by those whose authority he has hitherto been subject to and who exercised an influence on his life which he now believes he can do without. He distances himself from his role model, his mentor, who is often an older colleague. even if the latter helped him to enter or progress in his career, he feels that he no longer needs him or anyone… and that the time may have come to take his place!

The adult claims full autonomy and total independence. It wants to do itself, at the cost of freely accepted constraints, of a desired self-coercion. His will stiffens, he only counts on himself, on his own strengths and his own abilities, abandoning external support and help. The masters have nothing more to teach him, he can even openly enter into competition with them for the conquest of a position or a title; he wants to be his own master, sovereignly deciding his destiny. Individualism takes precedence over solidarity, often perceived as a form of alienation and dependence. You have to know what you want and what you are worth. Adults do not doubt the validity of their legitimate ambitions.

Dignity, intransigence, autonomy, independence, pride… in adulthood, the individual intends to express himself in his own way in all his irreducible singularity. At the start of the stage, it may be the “dynamic young executive”, the upstart bulldozer ready to crush everything on his way to achieve his ends, to break ties of affection, love and friendship to climb the social hierarchies. With maturity and lived in a less caricaturally outrageous way, the adult is also the one who escapes the will of others, the weight of fatality, the contingencies of the present situation to affirm his own will, without worrying about the opinion of others, indifferent to criticism. He verticalizes, there is no question for him of bending, of bending, of swallowing his ambitions, of renouncing his dignity.

There “deep morality”, which appears (if it appears) during adolescence, continues (ideally) to develop and enrich itself during adulthood, with however a certain return to conformist and normalizing morality: people over thirty years are more conservative than adolescents and adults under thirty. The adult in fact constructs his thought on theoretically rational criteria which emphasize respect for the majority will of the community, which is supposed to be essential for maintaining order in society. He is by experience but also intuitively convinced, deep down, of the fact that in the long term no social equilibrium can last without firmly established laws, and thus freely accepts to conform to these laws.

The adult admits, however, that there are circumstances in which the common law, which he respects to the highest degree, may come into conflict with other moral imperatives. It then reserves the right to involve a “conscience clause”, A “right to disobedience” which is not in his mind an act of indiscipline, but the determined affirmation of a high and uncompromising loyalty to himself and to the collective principles that he places above all. In his eyes, his possible rebellions are another way of showing his need to maintain, against the current when necessary, a certain moral order. Ideally, the moral conformism of the adult is a voluntary, deliberate, willed, thoughtful conformism which does not exclude intransigent questioning, sometimes legitimate, sometimes arbitrary, but always clear and inflexible… as are the law and the common morals.

Adult status therefore implies an acute awareness of collective realities. At best, it allows the individual to achieve a fair balance between his will to personal achievement, his individual freedom, and general laws. He agrees to submit to collective standards provided that they are as close as possible to the principles he has forged in his soul and conscience. Nothing to do with the conformism of the child between two and three years old, nourished by a pressing need to adapt to the rules of the social game and basically incapable of radically bringing it to trial, if necessary.

Between the ages of forty and fifty, adults are generally led to become lucidly aware of their professional possibilities, to reassess their aspirations as a teenager and young adult. He is more or less obliged to admit, if he continues on his current path, that there are objectives that he will never achieve, ambitions on which he must give up definitively. He thinks of the years he has already lived and those that remain to him, and can if he wants to assess himself with great lucidity. Past the carefree childhood and the ardent adolescence, concerned and ready to open up to all possibilities, past the first years of his adult life, he then realizes that his life now has the face of destiny. We don’t redo each other. We are what we are, definitely.

Whether he succeeded in his life or not, by comparing his present with his hopes and past projects, whether he says to himself that he has done all that one could by force of will and personal discipline does not change it. nothing: the dice are thrown and basically, the adult becomes aware that he is the object of an inevitable future. It cannot go back, except in a marginal and superficial way. It only remains for him to sweep the impossible dreams from his mind, to accept himself as he is and to try to be as intensely and authentically himself in the path he has chosen or which imposed on him by circumstances.

The integration of these learnings to which the Uranian age invites can induce different behaviors according to the character and the particular living conditions of each individual. For some, this age makes it possible to be satisfied with the fixed, established and recognized situation that one has managed to conquer. The adult then seeks to maintain at all costs his social status, his professional role, his situation in a given hierarchy. He asserts his high skills while taking refuge behind the acquired authority, at the risk of a lack of renewal, of a sclerosis of the activity that has become mechanical.

But for others, maturity can also give a frenzied taste for great individual adventures, where you play big and risk everything between audacity and recklessness. The last possible adventures before the physical decline brought about by old age: everything, rather than getting bogged down in routine, rather than the flat uniform rolling of the crowds. This adult has the insane or intuitive certainty that he can, by force of will, master his destiny. Whether he renounces impossible dreams or whether he decides to revolt against his destiny, the mature man has his wisdom: he must in any case tame himself, master himself, be proud of himself in despite everything, not to deviate from its objectives whatever the circumstances.

The important thing, in this case, is above all to note that from the age of forty, the adult occupies social roles “responsible” (whether as a parent or in his socio-professional life) where he largely decides for others: he is, in one way or another, at one level or another of the social hierarchies, a representative of the generation “the controls”, with the impression, rightly or wrongly, of being invested with an individual power over the collective which allows him to direct his own career, his own future but also that of others, to indicate the way forward, to decide the route.

At this age, whether or not he has succeeded in accomplishing his individual objectives up to his initial expectations, the adult feels very concerned for the next generation. He is concerned with guiding, teaching, showing the way, believing that he is wise, competent and experienced enough, that he has forged a sufficiently structured and synthetic vision of the world for this. The adult becomes the master and, ideally, applies to his masterful teaching his qualities of discipline, wisdom and self-control, knowing that he is more capable and more experienced in making the best possible choices in life.

The adult controls his affectivity as the power of his instincts diminishes and his physical strength diminishes. He learns to no longer let his emotions take precedence over his organized brain, which allows him to make colder and more lucid decisions, matured for a long time away from the disorders of the heart and the senses. Moreover, throughout the Uranian stage there is desexualization, cerebralization or spiritualization of human relationships: the adult is the one who is able to consider others as individuals, and not as objects of libidinal investment, of sexual desire.

The adult who has reached his full development can therefore behave like a true experienced guide, respected and listened to for the organized clarity of his vision of the world, for his perspective, his ability to find simple answers to complex problems, for his enlightened and infallible authority, for his rigor and his strength of character… Let’s face it, it’s rare. Evolution is an obstacle course, and there are many adults for whom it ends between the ages of forty and fifty, and who therefore give up the game, refusing to renew themselves. The risk of the adult is to freeze, to harden, to fix themselves in immutable habits of thought, to close themselves to new ideas, to let themselves be dominated by all the answers they have found. to the problems in life.

It is then said of old people that they drool, that they are suffering from mental or psychic deafness. We then think of the sinister figure of the senile, atrabilary, arthritic and embittered old man who imposes a desiccated and sclerotic vision of the world (“It was better in my day!”), to the irremovable and indestructible mandarin clinging to his hard-won authority, no longer supporting the slightest contradiction. The adult who ages badly, far from behaving as an experienced guide, endlessly dwells on the same certainties as outdated as they are authoritarian, no longer knows how to listen to others, refuses to admit facts that contradict his peremptory affirmations, no longer knows how to be moved, no longer lets his heart express itself.

The eighty-four years of the sidereal cycle of Uranus cover for the majority of us the probable duration of our earthly life. Under the reign of Uranus, old age and then death await us. At the last stage of life, when time is short and the fatal deadline approaches, the adult has no choice but between despair and personal integrity. Despair reaches those who have not been able to give deep meaning to their lives: their death then appears to them as meaningless too. It is difficult to die peacefully and with dignity when you are convinced that you have wasted your life. One then retracts into the hard shell of a “me I” who refuses to die. In a last burst of egocentric and desperate narcissism, we exclaim “why me?”, by refusing to consider that death is the common law.

But at the end of his development, we also observe in the old man, according to Erikson, a “post-narcissistic love of the ego in general (not of one’s own personality) as a spiritual experience with universal meaning. This love of self involves acceptance of the past life, with no regrets for dreams that were not realized or for experiences that might have been different.” On the verge of death, an authentic serenity appears, the pride of accomplishment: man at the end of the Uranian stage has found an individual meaning in the universality of Being, independently of the material contingencies of existence. He admits to being and having been only a fleeting individual crystallization within the great unknown of the universe. Stripped of all desire, all affect, all regret, all remorse, all project, he leaves the peaceful world, knowing that he has fully succeeded in his duty of individuation by assuming with dignity and until the end his condition of male.

We are in uranian state, like adults aged 30 to 84, when we have heightened awareness of our individuality, our singularity, our originality, when we are convinced that our independence, our autonomy, our free will, our will to decide for we ourselves of what concerns us can suffer no limitation, no compromise, no restriction. We are in a Uranian state when we have such inflexible demands, such deep motivations, such indisputable goals that there is no question for us of bending before adverse circumstances, of abdicating our ambitions in the name of a any short-sighted realism, to accept adjustments to our situation that would only be betrayals.

We are still in a Uranian state when we refuse half-measures, waltz-hesitations, timorous caution, when we take in our soul and conscience decisions that we would like to be definitive, without appeal, without nuances, heavy with consequences. We are in a Uranian state when our will is entirely directed towards an exclusive objective of any other, when we show an unfailing determination and authority to achieve our ends, when we decide to follow without weakening an itinerary rectilinear by engaging fully and totally our individual responsibility by being intimately convinced that we are right.

We are always in a Uranian state when we demonstrate an implacable seriousness, a punctilious rigor, a systematic discipline to program our goals, our objectives, our activities, when we claim our sharp skills, our design efficiency, our ability to simplify the complex. We are in a Uranian state when we reject vagueness and approximation in the name of an ideal of clarity, extreme precision, absolute conciseness, when we specialize excessively, when we polarize our attention to achieve maximum efficiency. We are in a Uranian state when we believe that any thought or activity must be strictly formulated, hierarchized, codified so that nothing is left to chance.

We are finally in a Uranian state when we behave with confidence, originality, independence, when we have an acute sense of our own dignity, when we affirm our individuality or our individualism in its deepest, most basic, more inalienable. We are in a Uranian state when we are convinced that we are infallible, when we impose ourselves and our views without hesitation, when we take an unambiguous position in the midst of confused debates, when we believe that our certainties and decisions always proceed from a rational logic which no one should oppose or find fault with. We are in a Uranian state when we experience exceptional moments when we have to bet everything.

Individuals whose natal chart reveals a strong and dominant Uranus have fixed convictions, a powerful perception of their individual requirements, a natural intransigence which encourages them to assert their independence and their authority with an often brittle aplomb. Those whose birth chart does not value Uranus have more difficulty than average in making radical decisions, in playing the card of cavalier individualism. They most often refuse to indulge in exacerbated voluntarism, find it difficult to rigorously and systematically program their thoughts and activities and can shirk when it comes to openly affirming their specific discourse.

▶ The Uranian: Psychological profile

▶ The uranian function ‘rT’ (representation of Transcendence)

▶ Uranus-Neptune-Pluto: extensive Transcendence

▶ Sun-Jupiter-Uranus: intensive representation

▶ Uranus

▶ Introduction to the Theory of Planetary Ages

▶ L’échéancier planétaire et la Théorie des âges

Les significations planétaires

par

620 pages. Illustrations en couleur.

La décision de ne traiter dans ce livre que des significations planétaires ne repose pas sur une sous-estimation du rôle des Signes du zodiaque et des Maisons. Le traditionnel trio Planètes-Zodiaque-Maisons est en effet l’expression d’une structure qui classe ces trois plans selon leur ordre de préséance et dans ce triptyque hiérarchisé, les Planètes occupent le premier rang.

La première partie de ce livre rassemble donc, sous une forme abondamment illustrée de schémas pédagogiques et tableaux explicatifs, une édition originale revue, augmentée et actualisée des textes consacrés aux significations planétaires telles qu’elles ont été définies par l’astrologie conditionaliste et une présentation détaillée des méthodes de hiérarchisation planétaire et d’interprétation accompagnées de nombreux exemples concrets illustrés par des Thèmes de célébrités.

La deuxième partie est consacrée, d’une part à une présentation critique des fondements traditionnels des significations planétaires, d’autre part à une présentation des rapports entre signaux et symboles, astrologie et psychologie. Enfin, la troisième partie présente brièvement les racines astrométriques des significations planétaires… et propose une voie de sortie de l’astrologie pour accéder à une plus vaste dimension noologique et spirituelle qui la prolonge et la contient.

Téléchargez-le dès maintenant dans notre boutique

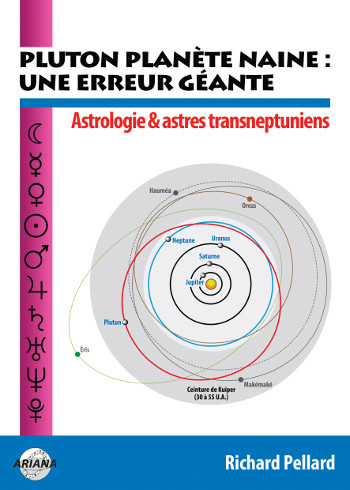

Pluton planète naine : une erreur géante

par

117 pages. Illustrations en couleur.

Pluton ne fait plus partie des planètes majeures de notre système solaire : telle est la décision prise par une infime minorité d’astronomes lors de l’Assemblée Générale de l’Union Astronomique Internationale qui s’est tenue à Prague en août 2006. Elle est reléguée au rang de “planète naine”, au même titre que les nombreux astres découverts au-delà de son orbite.

Ce livre récapitule et analyse en détail le pourquoi et le comment de cette incroyable et irrationnelle décision contestée par de très nombreux astronomes de premier plan. Quelles sont les effets de cette “nanification” de Pluton sur son statut astrologique ? Faut-il remettre en question son influence et ses significations astro-psychologiques qui semblaient avérées depuis sa découverte en 1930 ? Les “plutoniens” ont-ils cessé d’exister depuis cette décision charlatanesque ? Ce livre pose également le problème des astres transplutoniens nouvellement découverts. Quel statut astrologique et quelles influences et significations précises leur accorder ?

Enfin, cet ouvrage propose une vision unitaire du système solaire qui démontre, chiffes et arguments rationnels à l’appui, que Pluton en est toujours un élément essentiel, ce qui est loin d’être le cas pour les autres astres au-delà de son orbite. Après avoir lu ce livre, vous saurez quoi répondre à ceux qui pensent avoir trouvé, avec l’exclusion de Pluton du cortège planétaire traditionnel, un nouvel argument contre l’astrologie !

Téléchargez-le dès maintenant dans notre boutique