Your Planets

Portraits of the Planets

Aspects between Planets

The planetary ages

The planetary families

Planets in Signs

The Planets in comics

For more than 2500 years astrologers have had only one concept intuitive and empirical of what the objective reality of an Aspect is. They confined themselves to observing empirically certain real effects and imagining unreal ones. Very rare and very embryonic have been the attempts at conceptualization and therefore at theorization, such as that exposed by Ptolemy in the 2nd century and that proposed by Kepler in the 17th. Both resulted in erroneous explanations and failures. It is only in the 20th century that the concept of Aspect began to be truly elaborate, making it possible to distinguish the true from the false in the antique and traditional notions and formulate a rational explanatory theory through an overall conception of astrology. The contemporary design and graphical representation of the Aspects are the product of a long history, and the very idea of Aspect has evolved over the millennia.

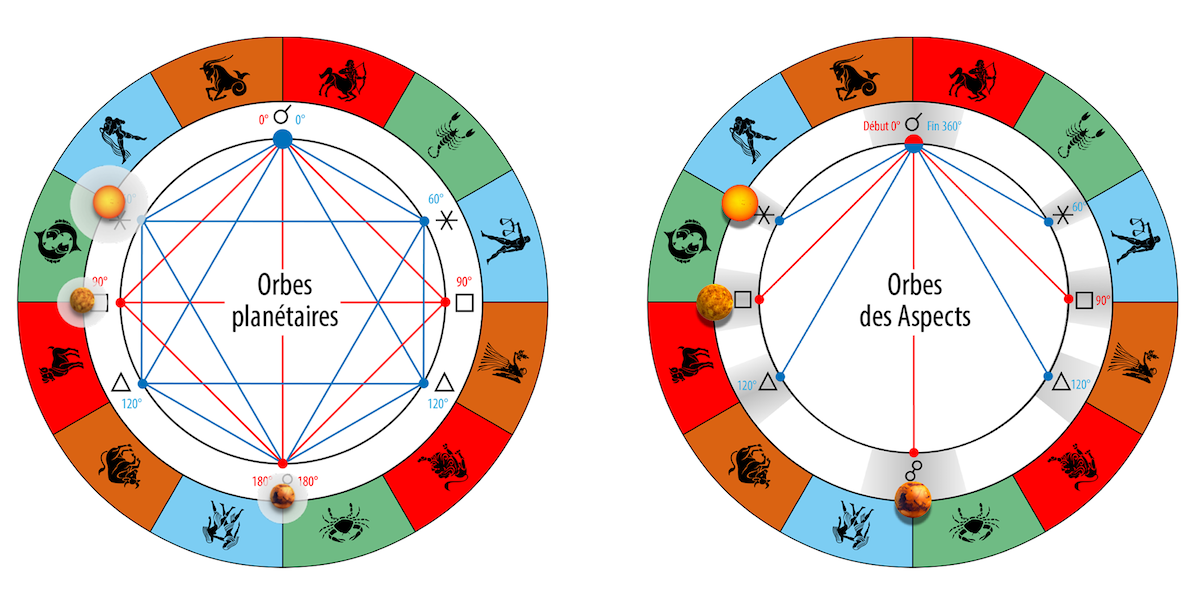

The planetary Aspects are now clearly identified as such by a minority of learned astrologers, and not as dependencies of the Ptolemaic zodiacal geometry, even if the latter retains some influence on their definition and on the admitted orbs. Theoretical debates about them will henceforth focus a lot about orbs and a tiny bit about ecliptic latitudes. To calculate the Aspects with or without an orb and whatever the extent admitted for it, the majority of astrologers retain their preference for the longitude reference.

Only the French doctor, mathematician and astrologer Jean-Baptiste Morin de Villefranche (1583–1656), a contemporary of Kepler, seems to have been interested in the problem of latitudes. He advocated in his writings that they be taken into account, but seems to have never observed this recommendation in his practice. But we are not sure that the works of this controversial character, first and last official royal astrologer, inventor of a method for calculating… lunar longitudes intended for maritime navigation, were indeed written by him. And even if that were the case, it is not impossible that this man of power, an expert in useful and above all useless controversies, and whose astrological writings show great intellectual confusion, did not position himself for the latitudes ecliptic only in order to distinguish themselves. But we will never be sure about this.

If Kepler clearly describes the Aspects in terms of the number of degrees of ecliptic longitude, and not based on the number of Signs which separated the Planets thus separated or connected, this is not the case, far from it, of all the 17th century astrologers and beyond. The influence of the Ptolemaic conception remains extremely significant, and the majority of astrologers still refuse to accept the relevance and reality of planetary Aspects when they do not occur in Signs which are not separated by a zodiac angle privileged.

From this perspective, the problem of orbs, which is above all designed as that of their stretches, is gradually gaining in importance. Should we accept that two planets located at 2° from each other are in conjunction, whereas they are in two Signs of different Elemental nature, for example Fire Sagittarius and Earth Capricorn? Is there really a square with an orb of 5° between a planet at 28° Aquarius and another at 3° Gemini, both Air Signs therefore connected zodiacally by a trine of 120°? In summary, should orbs be accepted only for planets whose Aspect they form is identical to that of the Signs in which they are found, or do the orbs apply regardless of the Signs in which the planets in question are located? Aspect? The debates are raging and no consensus is emerging on this crucial subject. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that the preeminence of orbs over Signs by most astrologers.

Another problem could have been at the center of a debate: that of the origin and therefore of the root cause orbs. Are they induced by the planets themselves, or are they an effect of their Aspects? However, this question only seems to have arisen for a minority: the others are convinced that the extent of the orbs varies depending on the planets involved. The astrologer William Lilly, (1602–1681) for example, recommends, after esoteric calculations and whatever the Aspect, a rounded orb of 15° for the Sun, 12° for the Moon, 7° for Mercury, Venus and Mars, and 9° for Jupiter and Saturn. In his system, when two planets have different orbs, he adds them and then divides them by two. Thus, for example, any Sun-Mars Aspect admits an orb of (15 + 7)/2 = 11°. Note in passing that Lilly considers that the parallel of declination (position of two stars on the same degree of North or South declination) is an Aspect, and he even considers that it is the most important of all. But he was almost the only one to think so… Note here that the parallel of declination is measured on the equator, and not on the ecliptic like the Aspects.

Finally, it goes without saying that other astrologers proposed many other orbs based on the same system. Their extents were mostly determined either by computational methods arbitrary based on fanciful astrometric or arithmological data guided by certain personal observations (such as those of Lilly), or by intuition pifometric based on questionable practices. These systems are based on the assumption that it was the planets that defined their orbs, they more or less overvalued all orbs of sextiles, squares and trines. We will have to wait for the 20th century so that finally the orbs depend on the Aspects themselves, independently of the planets which these unite or separate or in association with them.

This new interest in the Planetary Aspects, their accuracy and their orbs counted in ecliptic longitudes of the celestial sphere quickly moved and transposed to the Aspects formed between the planets and the 4 Major Angles of the local sphere (AS, MC, DS, IC). These 4 Angles being also the cusps (beginnings) of Houses I, X, VII & IV, this transposition of the Aspects then spread to all the cusps of the other Houses.

Relaying the observations of generations of astrologers who had preceded him, Ptolemy indicated in his Tetrabiblos that the proximity of the planets with respect to the horizon (axis of angles AS-DS) and the meridian (axis of angles MC-IC) was a determining factor in the evaluation of their relative potency in a Chart. This subject being developed in the article on Ptolemy and the error of the senestrogyrate houses, there is no need to do so here. Let us only point out, because it is important, that this proximity was not for Ptolemy synonymous with “Aspect”, but of “presence” in a defined place in the local sphere. As noted earlier, the word “Aspect” is absent from Ptolemaic terminology. Expressions such as “Venus at the trine of the Ascendant” or “Moon squared cusp of House VIII” were totally to him foreign.

17th-century astrologers therefore invent the “Aspects to Angles”. The proximity with regard to the Angles being, with the planetary Masteries over the Signs, one of the two main factors serving as a criterion for the selection of the dominant planets, the Aspects to the Angles, and quite particularly to the AS then to the MC, will become new indicators of relative planetary powers. The Ptolemaic proximity of a planet to an Angle is thus transformed into “conjunction”. From now on, we can state that “Saturn conjunct the Ascendant” or even that “Mercury is at the trine of the Midheaven” and draw the conclusion that Saturn and Mercury are very important in a Chart displaying this particularity. In the case of Saturn, why not, since this planet is then angular, a position that can be defined, either by its presence near the AS, or by its conjunction with it if the orb of presence and conjunction are the same. But in the case of Mercury, if it is not also angular in addition to being at the trine of the MC, it is very debatable, because the concept of Aspect at the Angles is itself very debatable and very hypothetical.

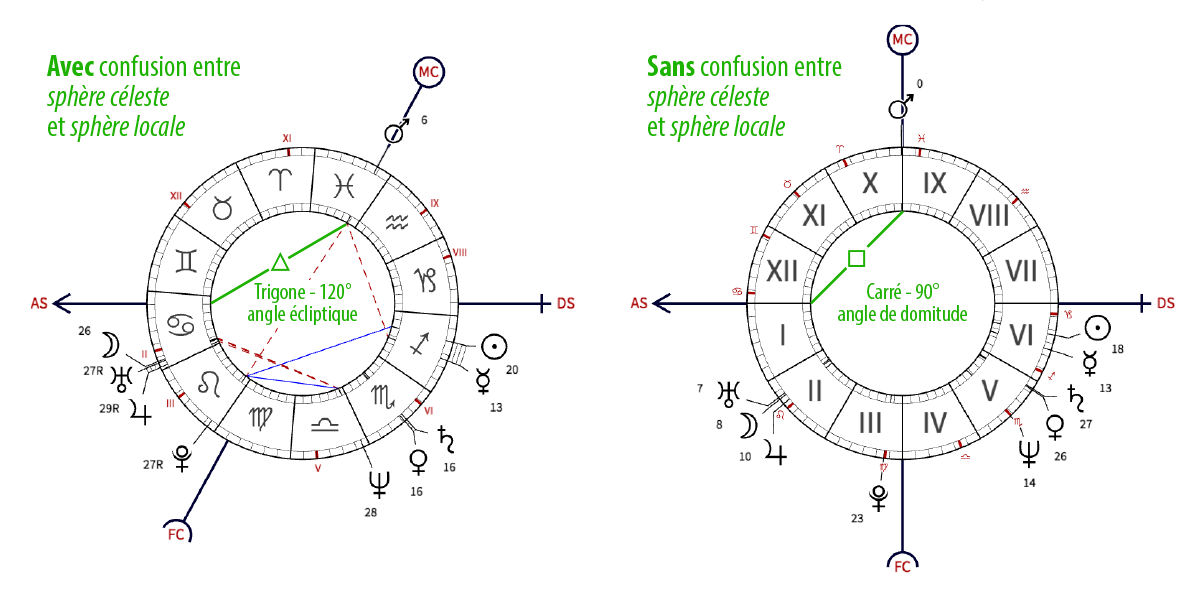

These Planetary aspects at angles newly imagined pose serious problems. They are based on the transposition in the local sphere of planetary positions calculated on the ecliptic. However, in the local sphere, whose two major planes are the horizon (AS-DS axis) and the meridian (MC-IC axis), the ecliptic is in permanent rotation and its inclination on the horizon (therefore the height of the MC and of the IC and of the Signs that these intercept) varies according to the terrestrial latitudes, but also annually and according to each hour and minute of a day. Then there is the problem of representation of the Chart in two dimensions which is obtained by inserting the ecliptic in the local sphere. If it wants to translate the inclination of the ecliptic on the horizon, this representation of the local sky must necessarily create ecliptic angles between the horizon and the meridian, which are perpendicular and whose angle which separates them is therefore 90°.

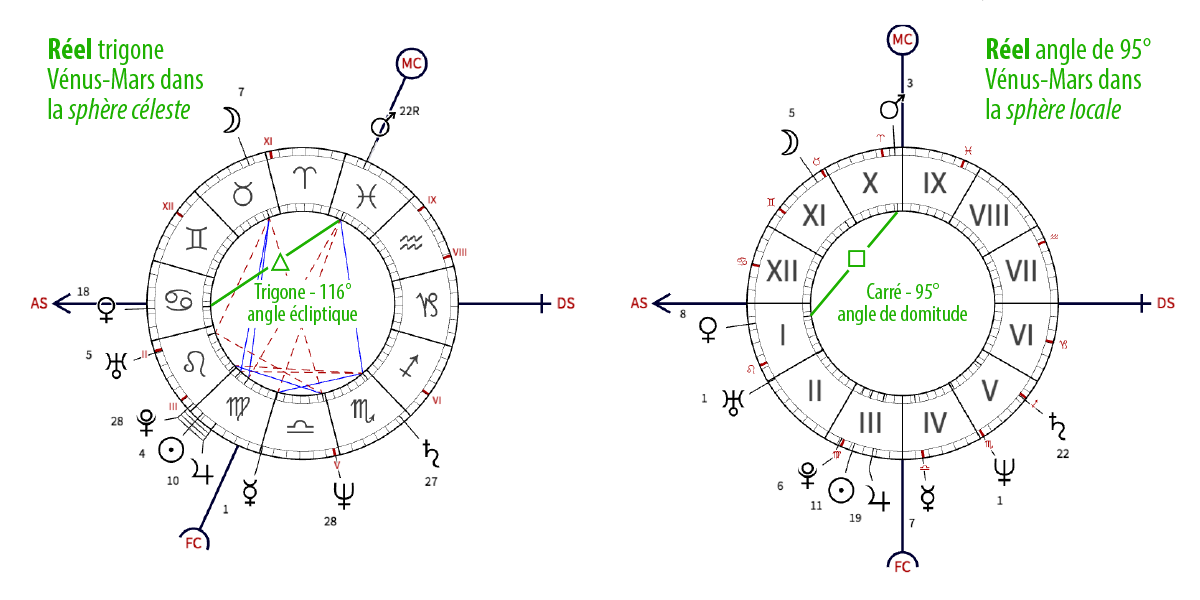

This representation of the sky can make believe, for example, that the MC can, at certain times of the day and under a terrestrial latitude of approximately 45° North or South, be in Aspect of trine (120°) to the AS. From a planet then located exactly at the MC, for example Mars in Pisces, we will then say that it is in trine with AS early Cancer. But in the reality of the local sphere, this Mars in culmination at the upper meridian is then perpendicular to the horizon and therefore forms an angle of 90° (identical to that of a square) with the same Ascendant at the beginning of Cancer. By a sleight of hand caused by the artifices of a particular representation of the sky, an angle of 90° has been replaced by another of 120° which measures the same position, but considered from two… different angles (!). And it is of course the same for the Charts which display an angular distance of 60° (equivalent to a sextile) between the AS and the MC. Only Charts with an AS at the end of Virgo or the beginning of Libra escape this spell induced by this type of representation. Indeed, in these particular cases it locates the MC perpendicularly (90°) to the AS.

The question that then arises is which angle to choose: 90° or 120°? If we opt for 120°, we are faithful to the ecliptic arc qualified as the Aspect of trine between Mars/Pisces exactly at the MC and the AS at the beginning of Cancer, but we are unfaithful to the local sphere arc of 90° which is not an Aspect. And if, on the contrary, we opt for 90°, the Mars-AS trine vanishes in the mirages of the representation that made it happen. There is no middle ground. We cannot cut this celestial pear in two and put (120° + 90°)/2 = 105° to make allowances for these things: that makes no astrometric sense. 17th-century astrologers have chosen, whether they asked themselves this question or not, and it seems that they did not. Always keeping the same example, they opted for Mars/Pisces exactly at the MC at the trigone (120°) of the early AS Cancer in ecliptic longitude, and against Mars in higher culmination at the meridian therefore perpendicular (90°) to the AS in the local sphere.

The example of Mars/Pisces at the MC trine to AS Cancer illustrates a case that is not serious in the use of the so-called “Aspects to Angles”, since after all it is an angular Mars. It is not the same if we consider that a non-angular planet: taking into account these “Aspects to Angles” can then lead to giving it an exaggerated importance and therefore distort the interpretation of this Chart. And there is even worse in the delusions inspired by the “Aspects to Angles”: Those are the “Aspects at cusps” of all the Houses. Thus, for example, a Saturn squared (90°) of the cusp of House II (devolved by tradition to money and possessions) was supposed to inform about the relationship to this kind of thing of the Subject having this “Aspect” in his Natal Chart and/or in Transit. This is exactly the kind of nonsense that Kepler flatly rejected.

Let us point out in passing that William Lilly proposed an orb of 5° for all the Aspects at the Angles and at the cusps, which is totally absurd given that the cusps (beginnings of the Houses), apart from those of the angular Houses I-X-VII-IV, vary considerably depending on the housing systems used. Unfortunately the so-called “Aspects to Angles” born at this time and their orbs, very variable according to the astrologers, flourished and they are still used in the 21st century.

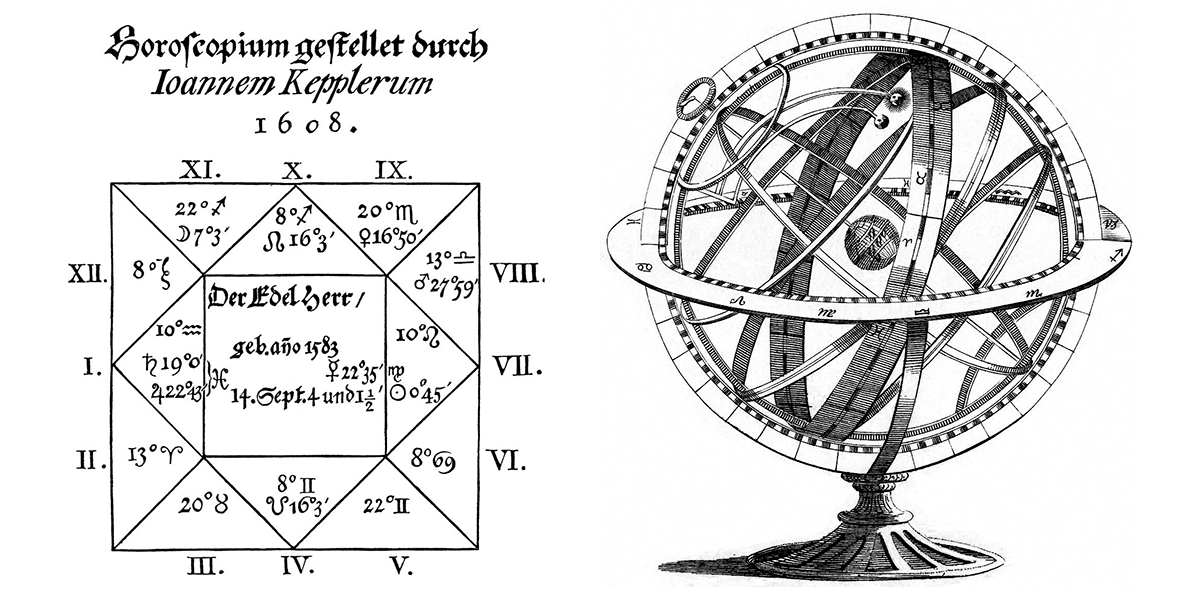

To conclude this demonstration, it should be noted that the sky charts used by astrologers before the 20th century were very different from those whose graphic format subsequently prevailed. of a rectangular or square shape, they represented very schematically only triangular Houses of equal extents inside which the degrees of the cusps (points of the Houses) and of the planetary positions were inscribed. Neither the ecliptic, nor the horizon, nor the meridian were clearly represented. The figure below on the left is one example dating from the 17th century. It is obvious that such a type of hyper-abstract representation of the Natal Chart distorts the perception that one may have of the astronomical realities that it is supposed to express. And that it can thus and also contribute to distorting our conceptions as well. And that was probably the case with most serious astrologers, even if they had armillary spheres (figure below right) to see the astrological-astronomical real in three dimensions. As for the others… the printed ephemerides and the tables of Houses allowed them to design anything without worrying about astronomical reality.

The design of the planetary Aspects and the pseudo-Aspects at the Angles has changed little from the 17th to the 20th century. Most astrologers used some Minor Aspects of Kepler in addition to the Major Aspects and some did not. All of them used the pseudo-Aspects at the Angles. The ecliptic latitudes of the planets were still not taken into account to calculate these Aspects, or even only mentioned because of the problems they can cause. The orbs were arbitrarily set by the planets. No truly systematic theory of the Aspects and their orbs has been formulated. As Michael Freedman notes in his article A historical study of the use of Aspects, “until 1900, astrology was still effectively in the Middle Ages. Kepler had had some influence and other great astrologers, such as Placidus, had played a considerable role in the development of this art. Nevertheless, reading astrological books as recent as those of Wilson and Pearce” [19th century English astrologers], “it is to leave the modern world to return to ancient astrology.”

▶ Aspects theory and practice

▶ Les aspects, phases d’un cycle

▶ Aspects : existe-t-il un modèle traditionnel ?

▶ Aspects : théorie et bilan conditionaliste

▶ Introduction à l’interprétation des aspects

▶ The planetary Aspects and their orbs

▶ Les Aspects kepleriens

▶ Les “aspects” aux Angles

▶ Chronologie des Aspects et Transits

▶ Les Aspects planétaires

Les significations planétaires

par

620 pages. Illustrations en couleur.

La décision de ne traiter dans ce livre que des significations planétaires ne repose pas sur une sous-estimation du rôle des Signes du zodiaque et des Maisons. Le traditionnel trio Planètes-Zodiaque-Maisons est en effet l’expression d’une structure qui classe ces trois plans selon leur ordre de préséance et dans ce triptyque hiérarchisé, les Planètes occupent le premier rang.

La première partie de ce livre rassemble donc, sous une forme abondamment illustrée de schémas pédagogiques et tableaux explicatifs, une édition originale revue, augmentée et actualisée des textes consacrés aux significations planétaires telles qu’elles ont été définies par l’astrologie conditionaliste et une présentation détaillée des méthodes de hiérarchisation planétaire et d’interprétation accompagnées de nombreux exemples concrets illustrés par des Thèmes de célébrités.

La deuxième partie est consacrée, d’une part à une présentation critique des fondements traditionnels des significations planétaires, d’autre part à une présentation des rapports entre signaux et symboles, astrologie et psychologie. Enfin, la troisième partie présente brièvement les racines astrométriques des significations planétaires… et propose une voie de sortie de l’astrologie pour accéder à une plus vaste dimension noologique et spirituelle qui la prolonge et la contient.

Téléchargez-le dès maintenant dans notre boutique

Pluton planète naine : une erreur géante

par

117 pages. Illustrations en couleur.

Pluton ne fait plus partie des planètes majeures de notre système solaire : telle est la décision prise par une infime minorité d’astronomes lors de l’Assemblée Générale de l’Union Astronomique Internationale qui s’est tenue à Prague en août 2006. Elle est reléguée au rang de “planète naine”, au même titre que les nombreux astres découverts au-delà de son orbite.

Ce livre récapitule et analyse en détail le pourquoi et le comment de cette incroyable et irrationnelle décision contestée par de très nombreux astronomes de premier plan. Quelles sont les effets de cette “nanification” de Pluton sur son statut astrologique ? Faut-il remettre en question son influence et ses significations astro-psychologiques qui semblaient avérées depuis sa découverte en 1930 ? Les “plutoniens” ont-ils cessé d’exister depuis cette décision charlatanesque ? Ce livre pose également le problème des astres transplutoniens nouvellement découverts. Quel statut astrologique et quelles influences et significations précises leur accorder ?

Enfin, cet ouvrage propose une vision unitaire du système solaire qui démontre, chiffes et arguments rationnels à l’appui, que Pluton en est toujours un élément essentiel, ce qui est loin d’être le cas pour les autres astres au-delà de son orbite. Après avoir lu ce livre, vous saurez quoi répondre à ceux qui pensent avoir trouvé, avec l’exclusion de Pluton du cortège planétaire traditionnel, un nouvel argument contre l’astrologie !

Téléchargez-le dès maintenant dans notre boutique