Your Planets

Portraits of the Planets

Aspects between Planets

The planetary ages

The planetary families

Planets in Signs

The Planets in comics

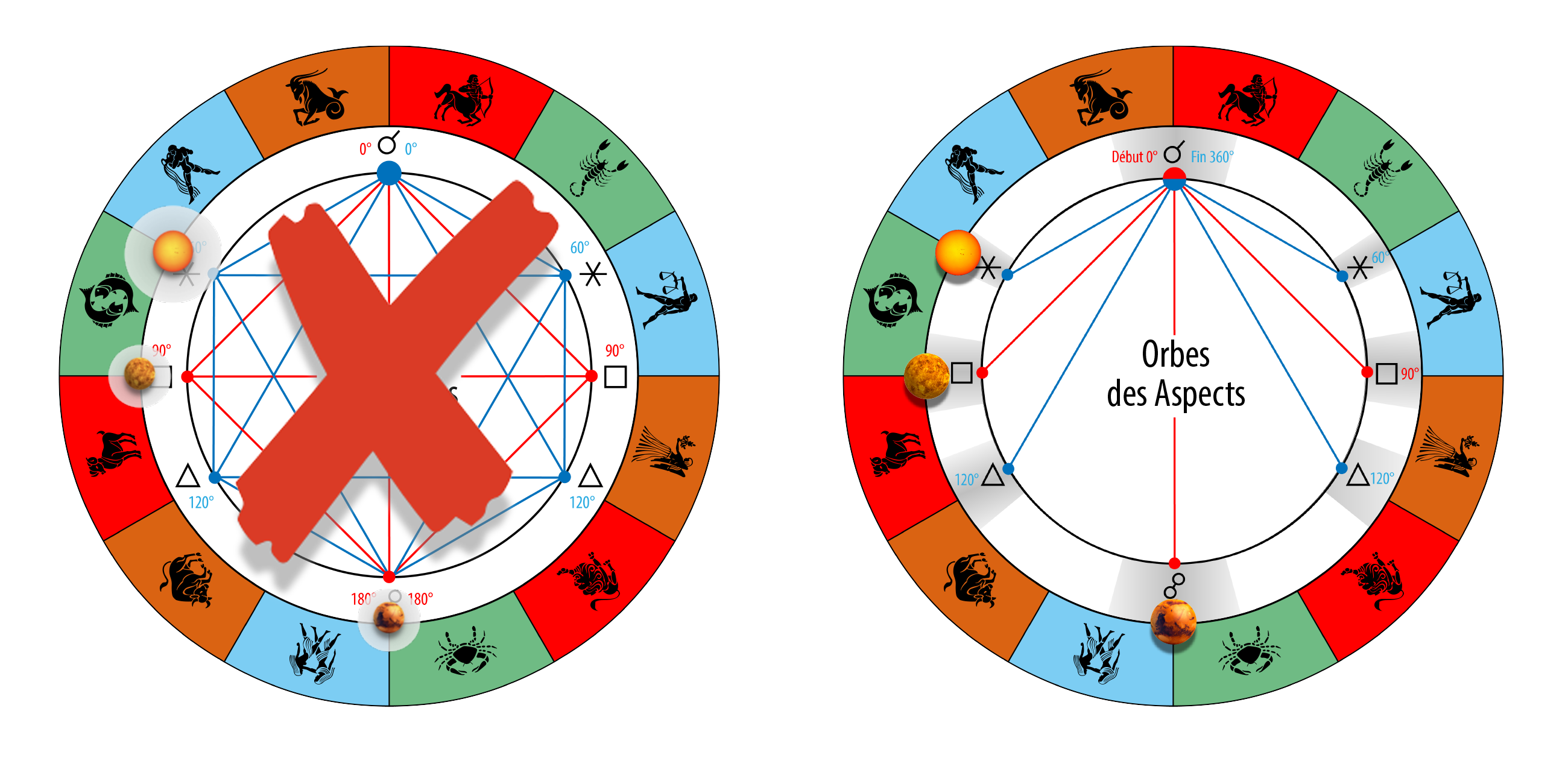

For more than 2500 years astrologers have had only one concept intuitive and empirical of what the objective reality of an Aspect is. They confined themselves to observing empirically certain real effects and imagining unreal ones. Very rare and very embryonic have been the attempts at conceptualization and therefore at theorization, such as that exposed by Ptolemy in the 2nd century and that proposed by Kepler in the 17th. Both resulted in erroneous explanations and failures. It is only in the 20th century that the concept of Aspect began to be truly elaborate, making it possible to distinguish the true from the false in the antique and traditional notions and formulate a rational explanatory theory through an overall conception of astrology. The contemporary design and graphical representation of the Aspects are the product of a long history, and the very idea of Aspect has evolved over the millennia.

The end of the 19th and the very first years of the 20th century are seeing two major innovations in the conception and perception of the Aspects and their orbs. We have to conceptual revival to the English astrologers Zadkiel and Alan Leo, and the graphic renovation, therefore perceptive, to the French astrologer Paul Choisnard. They did not know each other and most likely were unaware of their respective works. However, the simultaneous alloy of the conceptual and the perceptual that they have achieved without knowing it has upset the vision of the Aspects which had prevailed for three centuries.

The video below (14′ 20″) is a commented animation of the advances of the 20th century.

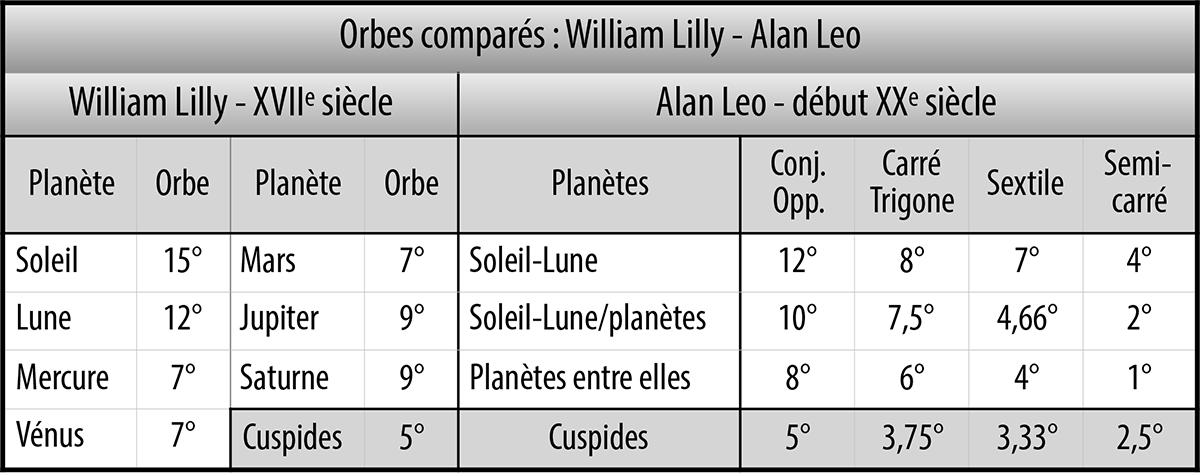

Let’s start with the conceptual innovation. The British Astrologer Zadkiel (Richard James Morrison (1795–1874) was the first, in his book The Handbook of Astrology published in 1861, to very clearly opt for orbs determined by the Aspects themselves. He distinguished the Aspects “parties” (exact) and the “plastics” (with orb) and proposed equal orbs of approximately 5º to 7º for all the planets whatever the Aspects (and still 10° for those with the Sun and the Moon), without further precision. Breaking with the tradition born in the 17th century, he no longer mentioned the extents of the planetary orbs determined by his predecessors only briefly, and purely indicatively, in a very brief astrological lexicon at the end of his book.

Was Zadkiel really the first to advocate this change of repository? We’ll never know. Let us note in passing and for the record that this former lieutenant of the Royal Navy, passionate about astro-meteorology and member of the very official Board of the Meteorological Society, also published in 1868 an article entitled The new Principle, or true system of astronomy, where the Earth is proven to be the motionless center of the solar system, which earned him a reputation as a charlatan (here well deserved) among scientists.

The design of the Zadkiel orbs was taken over (without mention of source) by the English theosophist and astrologer Alan Leo (1860–1917) in a article published in the first issue of The Astrologer’s Magazine in August 1890. Leo being much more well known and taken seriously than Zadkiel, he was finally credited with the authorship after he proposed in a manual his own system of orbs based on the Aspects rather than on the planets.

It was not a revolution, but a transition between the ancient and the modern, since these orbs of Aspects are in Leo modified by those still imposed in a rather important way by the planets involved in the Aspect (while Zadkiel was more radical). But now this new design was launched, and orbs related to Aspects alone could be designed, just as we could also design new planetary weights affecting the orbs, in a less considerable way than they did when they were imposed. without sharing. Of course, this design of the orbs met with severe opposition from traditionalists, but it eventually prevailed.

Before giving the orbs recommended by Leo, let us also point out that he made a serious cleaning in the profusion of Aspects used by too many astrologers of previous centuries. Very influenced by the work of Kepler, he nevertheless retains only 10, which is still a lot but constitutes real progress. They are the conjunction, the semi-sextile, the semi-square, the sextile, the square, the trine, the sesquisquare, the quincunx, the opposition and finally the parallel of declination. The latter is not not an Aspect strictly speaking, but it is in this category that he classifies this angular distance from the earth’s equator. In this list he could and should have eliminated the sesquisquare and the quincunx, which are not part of the same harmonic family as the others. But this discovery will not be made until about 60 years later. As for the other Keplerian aspects, “semi-sextile, quintile, bi-quintile, and those who are doubtful”, He thinks they “have no influence unless they are accurate to within a degree”.

We will pass here the calculations to which Alan Leo devotes himself to carry out his weightings between the part of orb caused by the planet and that induced by the Aspect itself. The table above shows the results. Leo’s orbs are compared to those of William Lilly two centuries earlier. In order not to overload it, the Minor Aspects after the semi-square have not been taken into account. Note that Leo often varied without his orb recommendations: this table only gives the most common version. In one of the other versions, for example, he goes so far as to advise a 17° orb for conjunctions with the Sun. Comparing Lilly’s and Leo’s orbs, we see that while granting more expansive orbs to the Sun and Moon than to the planets, he followed a decreasing logic in their assignment to the Aspects. This is a very great progress compared to past centuries, and others later will follow it in this unprecedented way.

By taking over Zadkiel’s idea, Alan Leo was associated with a major advancement in orb definition, of course, but that is only truly innovative contribution to astrology. He was a good popularizer of classical astrology, not a theoretician or a researcher. His vision of the orbs aside, his conceptions, beliefs and practices differed in no way from those of his contemporary colleagues, if only unlike them, for the most part focused on predictive astrology, he preferred to favor an essentially astro-psychological approach. But apart from these two points which made his originality, this theosophist in love with hermeticism was above all a conservative.

The astrologer, polytechnician and artillery soldier Paul Choisnard (1867–1930) is best known for being the originator of the first astro-statistical research, which was an innovation. His work was marred by serious methodological errors, and the results favorable to astrology which he thus obtained were subsequently both partially confirmed (for the extent of the zones of planetary angularity) and for the rest invalidated by more serious statisticians. But that is not what interests us here.

The representation of a thing, especially in a two-dimensional planar space, is always misleading. It only allows us to perceive this thing from a certain angle or… aspect, and therefore subsequently to conceive it according to this perception. We have already pointed out, in the section devoted to “Aspects to Angles”, how the flat images that we plaster on the real volumes could make us believe in the reality of the perceptual artifices thus produced. In short, as stated by the philosopher, engineer and semantician Alfred Korzybski, “the map is not the territory”, and we must be wary of our propensity to conceive multidimensional reality from the images that we place on it in an attempt, not only to figure it, but also to understand it.

The former artillery commander Choisnard is well placed to know that the military staff maps, developed at the beginning of the 19th century, were very useful for directing cannon fire on invisible targets, of which only the probable geographical position is known and whose altitude is shown by contour lines. He also knows that you have to take into account a number of other physical factors, which cannot be represented by a flat image, in order to achieve a successful shot on goal.

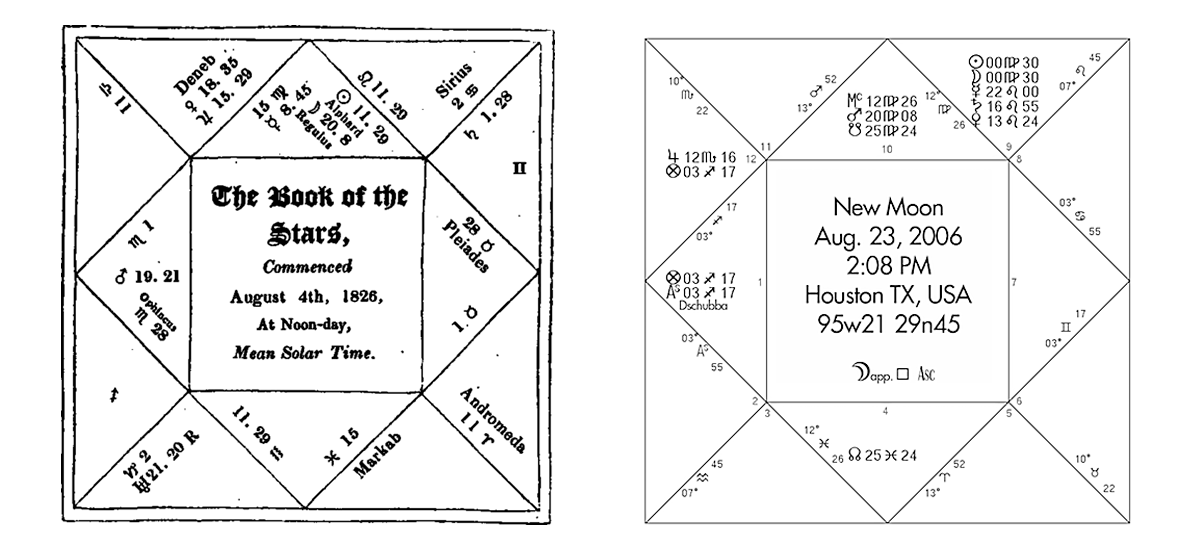

From the general staff map to the sky map, there is only one step for this former soldier turned astrologer, and he quickly takes it. Here is what he observed in 1921, having reflected on the traditional charts of the sky, in his book The representation of the sky in scientific astrology: “The Ancients represented the Chart by a square and triangles. The planets noted by their longitudes are shown at any location in their respective ‘Houses’. In short, instead of a zodiac, where all the variable elements are on it in their respective places — which immediately gives the idea of their set and their relationships — we have here a completely arbitrary representation, where the elements zodiacs, always noted according to their longitudes, are shown in places which correspond to nothing scientific. The old figure assumed the sky was projected onto the ecliptic but was careful (we never knew why?) to express this projection in its graph.”

The figures below illustrate these “Square charts”. The one on the left, which dates from 1826, is an example of the illegibility of this type of representation of star charts. The one on the right, just as little figurative and of an identical but more modern format, dates only from 2006 and shows that it still exists in the 21st century of astrologers who use it.

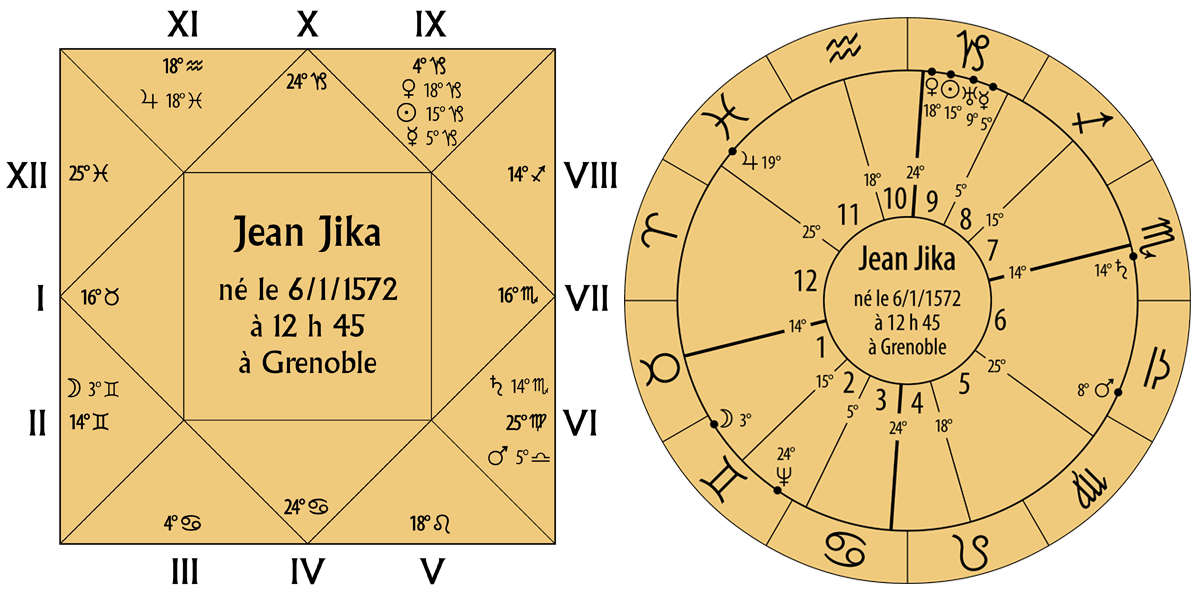

This quadrilateral representation of the Chart, which did not allow for a direct and synthetic perceptual experience of the configuration of the sky, was the subject of two timid reforms towards the end of the 19th century or beginning of the 20th century. Some astrologers are emboldened to create one circular version, but which was still focused on the Houses as it had been for at least twenty centuries. Then others ended up believing that this representation, whether its shape was quadrilateral or circular, excessively favored the Houses to the detriment of the zodiac. They therefore created a new circular representation of the Chart, in which the 12 Houses were surrounded by the zodiacal circle, where the planetary positions were noted on the ecliptic. But the representation of the Aspects was still absent there, since all the space inside the zodiacal circle was occupied by the situation of the planets in Houses, and the central circle had simply replaced the old central square to inscribe the natal data of the Chart.

Choisnard criticizes these cosmetic reforms: “Some modern astrologers replace the square figure of the Ancients with a slightly less obscure circular variant which should not be confused with our representation. It has, indeed, circular compartments but still like the old one reserved for the astrological Houses and not for the Signs of the zodiac. In summary, we are in the presence of two fundamental processes of representation having twelve compartments as a common basis: but these correspond for one to the Signs of the zodiac and for the other to the astrological Houses. In the old figure, in short, the elements of the zodiac were inscribed on the fixed Houses, while in the new one which I have admitted, the Houses were inscribed on an invariable zodiac.”

He himself has in fact opted for a more radical solution which makes him a pioneer of astrological cartography. He decided to position the Houses outside the zodiacal wheel and to keep only the discreet notation of their cusps which indicated their limits, as well as to clearly show the horizon and the meridian superimposed on the ecliptic plane; and finally he removed the central circle dedicated to data. In doing so, he has released in the center a vast space where he is now possible to represent the Aspects.

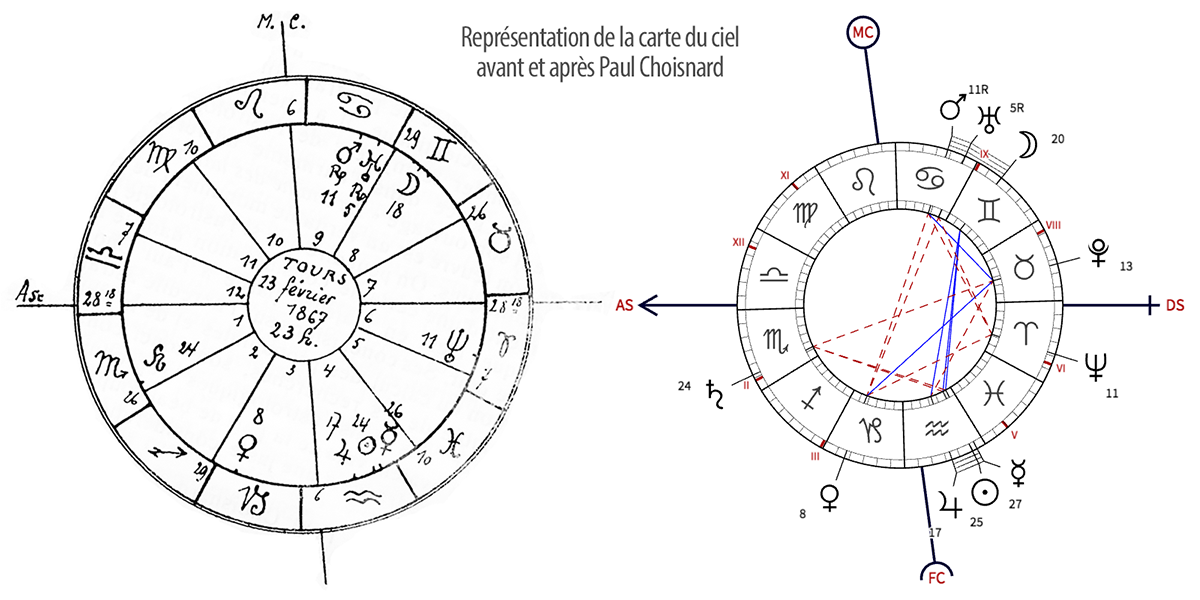

The two figures below illustrate this change of graphic reference. The one on the left represents the birth chart of Choisnard made in 1930 by the astrologer Gustave-Lambert Brahy, and the one on the right the same map produced by our software Astrosoft in 2019. We can easily see the similarities and differences. The one on the right conforms to Choisnard’s graphic revolution: it is much richer in directly perceptible information, it clearly highlights the Planets and their Aspects and therefore allows a better synthetic vision of the Chart. By looking at the one on the left, on the contrary, it is necessary to make a mental effort to be able to represent the systems of Aspects which connect the planets to each other. In certain circumstances, “a good sketch is better than a long speech” (phrase attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte).

Still in the same book in which he summarizes his decades of research, Choisnard confides that this graphic revolution did not happen overnight: “From the beginning of my work I was led for several years to join my ‘representation’ to the old figure with 12 triangles until the day when it seemed to me useless to keep the latter and when I definitively adopted a fixed zodiac to the exclusion of any other figure.”

Everything would have been for the best in the best of graphic worlds if he had not then had the idea, which he would never budge afterwards, of invariably positioning the zodiac at 0° Aries and to the left of the sky chart. He explains: “I consider it rational and of undeniable practical utility to orient the zodiac invariably. We must be logical: what is the purpose of the celestial figure? It has always essentially consisted in representing the Zodiacal Signs, the planets, the meridian, the horizon, the points of astrological Houses, and all the other elements we want, according to their geocentric longitudes. We reduce everything, in short, to a projection on the ecliptic. However, the geocentric longitude of an element of the sky being the arc of a circle which separates it from the equinoctial point 0° of Aries, it does not seem arbitrary at all to relate the measurements graphically to a fixed point of the figure representing precisely 0° Ram.”

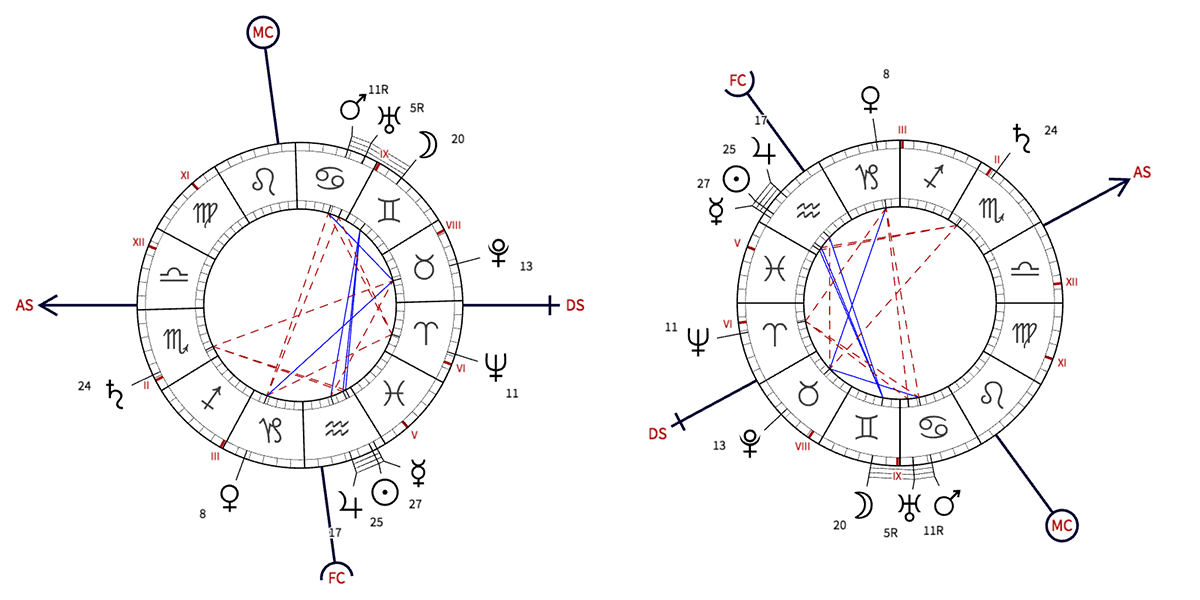

We should also point out that this representation, this time very questionable, since the horizon is now only sometimes… horizontal, also results from his choice to embark on statistical studies and thus to have a sky map whose zodiac is always oriented identically for comparison purposes. Which can only be understood if “we reduce everything, in short, to a projection on the ecliptic”. And what Choisnard got wrong about the planetary positions in the local sphere, which are also determined by ecliptic latitudes… but that’s a matter we’ll get to later. The two figures below illustrate this change in orientation leading to a… perceptual disorientation. In the left one, the horizon is horizontal, the AS on the left, the DS on the right, the upper culmination (MC) at the top and the lower culmination (IC) at the bottom. In the one on the right, which Choisnard finally preferred, the horizon is steeply inclined, the MC is found at the bottom and the IC at the top against all astronomical logic, but also perceptual.

Whether the fixed zodiacal reference point is the Ascendant (left chart) or 0° Aries (right chart), the new representations of the chart of the sky imagined by Choisnard have gradually imposed as an almost universal standard. The ancient figure composed of a square and 12 triangles, which had persisted for more than two millennia and shaped the conceptions and perceptions of generations of astrologers, is hardly used anymore. Choisnard would certainly have preferred the fixed zodiacal marker of 0° Aries to become the norm, but the perceptual logic of the horizontal horizon triumphed graphically: it is the one that is proposed by default in the display of the Charts of the quasi-totality of astrological software.

Paul Choisnard is neither a professional graphic designer nor an artist. He therefore did not make this radical change in the representation of the Charts on the basis of aesthetic choices. A polytechnician engineer by training, he did so with the aim of giving a relevant form to his desire to rationalize astrology and bring it into the field of scientific research, especially through statistical studies. To do this, he needs to enumerate and strictly classify the various factors that compose it. Artillery officer by profession, it seemed essential to him to have a map as precise and faithful as possible to rationally assess this territory that he intends to map in order to attack and conquer it. This is an unusual profile among astrologers, who for more than twenty centuries were generally recruited from astronomers, philosophers, mathematicians, theologians, poets or esotericists. And it was through the prism of this training and this job as a military engineer-gunner that he began to systematically study astrology in the early 1890s, when he retired from the army.

The engineer Choisnard begins by systematically listing the astrological factors of which he makes a reasoned inventory: “Limited choice, and at least provisional, of the simple factors in astrology, comprising three distinct classes: the 11 zodiacal positions, the 9 positions in Houses and the 54 angular distances. These 74 factors constitute a first basis of study already offering a very wide field of research, and relate to the clearest astronomical elements and the most accessible to statistics. The proposed method of investigation could also be applied to any other category of elements whose correspondence is sought.” The 11 positions in Signs are those of the AS, the MC and the 9 planets then known (Pluto will not be discovered until 1930, the year of the death of Choisnard). As for the 54 angular distances, they are related to the 36 Aspects between planets, of which he retains only the 6 major ones, and the 18 Aspects formed by the planets then known with the AS and the MC.

Since the focus here is primarily on the Aspects and their orbs, note that in this listed and quantified inventory, Choisnard gets rid of the Minor Aspects and at the cusps of the Houses, but retains those at the Ascendant and Midheaven. Breaking however with the prudential and compound system proposed by Leo, he openly adopts “for all the planets of a uniform and average orb to represent the angular limit of their reciprocal influence”. Note that this orb was variable for each Aspect: it is therefore the first to offer such a standardization of orbs based exclusively on Aspects. By making this unique and drastic decision to measure, he is probably showing a certain out of measure. But in doing so, he took a decisive step in the evolution of the concept of Aspect. From now on, the notion that the orbs are above all determined by the Aspects themselves will gradually prevail. And let us emphasize that by thus favoring the Aspects, both conceptually and graphically, he was in line with the Keplerian tradition, whose spirit if not the letter he admired and respected.

We should also point out that he makes a major distinction between the concept of Aspect And the one of presence of a planet close to AS, MC, DS and MC which defines its angularity, therefore its predominant character. For him this presence is not an Aspect, contrary to what most astrologers before him had come to think. He prefers to use the term “neighborhood”: “The maximum intensity corresponds to the vicinity of the meridian or the horizon to about 10° (in cardinal or cadent houses), MC and AS offering the most important places in this respect.” But paradoxically, he continues to use Aspects to Angles, which means that for him, a planet in the vicinity of an Angle is also in conjunction with it, which is contradictory. He did not explicitly and precisely mention this flagrant contradiction, which is unfortunate for the enemy of blur that he is.

Moreover, the statistics marred by methodological errors that he carried out to arrive at this conclusion nevertheless led him to identify that the angular planets were not located only in the Cardinal houses I-X-VII-IV thus considered as “strong” as Ptolemy indicated, but also in the Cadent houses XII-IX-VI-III, considered as “weak” and therefore devaluing for the planets that were located there. which was later confirmed by the Gauquelin statistics, which did not suffer from any methodological wanderings on this specific subject… In short, Choisnard thus made, fortuitously and through biased statistics, a fundamental discovery which should have been considered an artifact, but which nevertheless turned out to be correct!

Note in passing that this very modern emphasis on angularities before and after Angles of the local sphere did not prevent Choisnard from remaining very traditionalist and in his interpretation of the effects of these angularities, since immediately following his sentence quoted in the preceding paragraph, he did not hesitate to affirm that “Mars and Saturn in any one of these four so-called angular positions are bad. Jupiter or Venus, in MC and AS, are good.”

Artilleryman Choisnard may have had in mind, while carrying out his cartographic reform of the Charts, this writing by Lieutenant Colonel Borson, commissioned in 1868 to make topographical surveys in Savoy to improve the precision and fidelity of staff maps: “we will naturally seek to determine the crests by their striking points and to fix the position of the thalwegs. The general forms of the terrain and the secondary accidents will then be drawn more or less by sight, but care will be taken, in the most important stations, to draw one or more profiles, which will serve to preserve the lasting trace of the appearance of the places, and which, brought together and coordinated with others, will make it possible to obtain a fairly precise figure of the region.” This description can indeed be perfectly adapted to what can be expected from a sky map as close as possible to astronomical reality.

But Choisnard, in his new two-dimensional representation favoring the plane of the ecliptic, neglected the need to “draw one or more profiles” in the extremely important station that constitutes the local sphere. In other words, by privileging the cartography “front” of the ecliptic plane, he neglected the relief “in profile” induced by ecliptic latitudes. However, this real relief would have required the creation of a second type of sky map complementary to the first, in which the effect of this relief on the planetary positions in the local sphere could have been highlighted. But for him as already noted, “we reduce everything, in short, to a projection on the ecliptic”.

An example of this problem is given by Choisnard’s own Chart. In its projection on the ecliptic, Pluto is about 15° above the horizon in House VII. However, due to its strong ecliptic latitude (–15° 28′ S), it is actually about 8° from the same House, so much closer to the horizon than it seems, and even more if we also take into account its height (which is calculated independently of the Houses), which is +5° 24′. And it is not because he is unaware of the existence of this yet undiscovered planet (so he does not know that he was “plutonian”!) that he overlooks this important fact. Indeed, he knows that Venus could also have an important latitude (more than 8°) which can also affect its position in House and its height on the horizon. We will conclude that it was not at the end of what his business of cartographic renewal required: he should have imagined what later will be called the “House chart”, which takes into account the ecliptic latitudes and consequently allows to have a much more faithful and precise evaluation of the planetary positions in the local sphere.

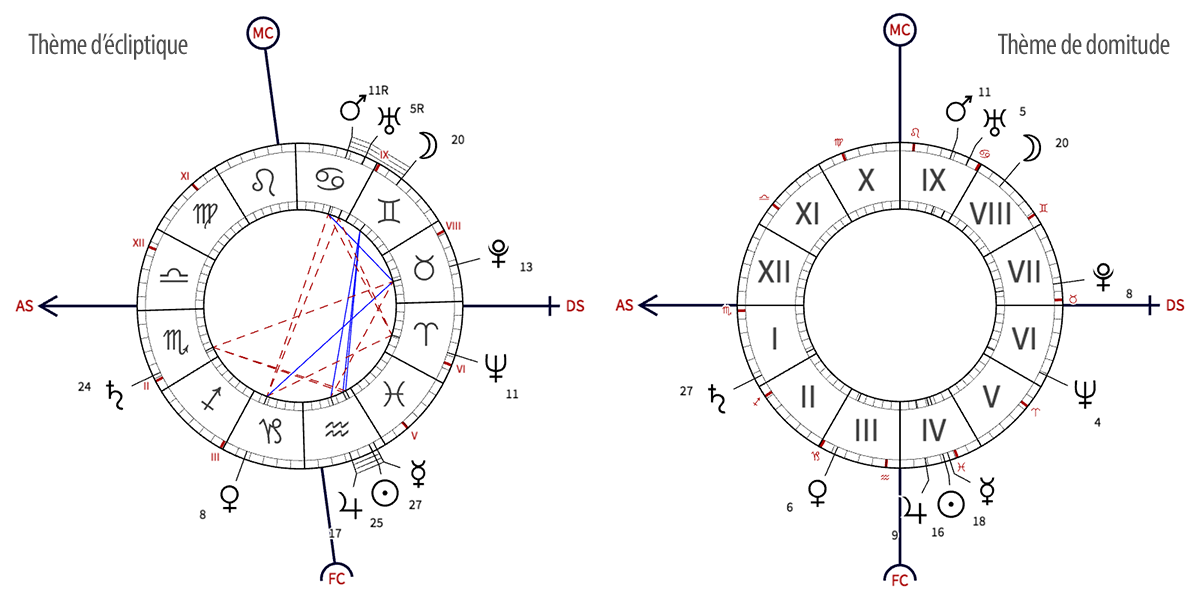

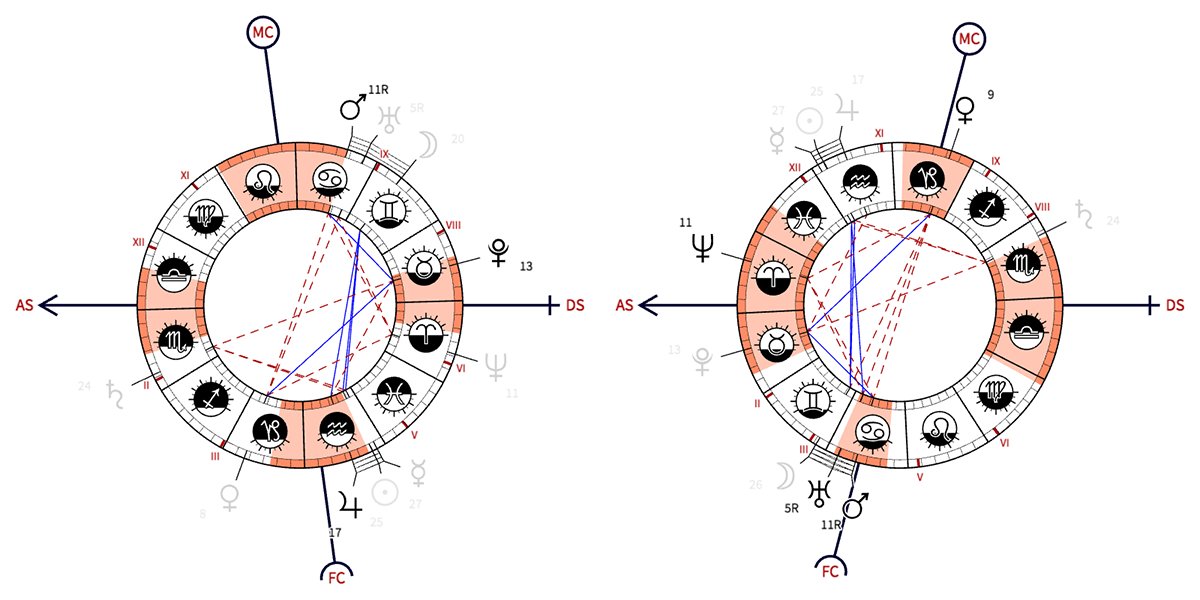

The graphs above represent the Ecliptic chart (left) and the House chart (right) by Paul Choisnard. In the Ecliptic chart, the 12 Signs have equal extents of 30°, but those of the Houses are unequal: this is a representation that favors the zodiacal reference plane. In the House chart, it is the opposite: the 12 Houses have equal extents, but those of the Signs are unequal: this sky map favors the reference plane of the local sphere. The Ecliptic chart provides information on the planetary positions in Signs and on the Aspects, but not on the real positions in Houses. The House chart provides information on the real planetary positions in Houses, but not on the zodiacal positions nor on the Aspects. The two maps are therefore necessary and complementary. Neglecting the house chart, in this example, can lead people to believe that Pluto is at 15° from House VII, when in reality it is at 8° and therefore much closer to the horizon.

Let’s go further in this latitudinal coordinate, but also in the temporal factor that Choisnard neglected. By stating that “the maximum intensity corresponds to the vicinity of the meridian or the horizon to approximately 10°”, he is seriously mistaken, not on the 10° orb before or after the two axes AS-DS and MC-IC thus defined, but on the referential which determines this orb. It calculates it in fact in degrees of ecliptic longitude, as if all of them were passing from East to West at the same speed.

However, it is not. Depending on the time of day, the same degree can for example, under a terrestrial latitude of 45°, be traversed in 6.66′ (6.66 minutes) or in 2.92′ of time, which means that not all degrees are equal in duration. If, like Choisnard, we determine the extent of these zones of angularity on the ecliptic — that is to say if we calculate them in number of degrees of ecliptic arc —, we must then take this factor into account. And this astronomical and temporal factor requires that these orbs of angularity be wider for degrees of zodiacal longitude traveled in 2.92′ of time, and narrower if traveled in 6.66′. But if, on the contrary, we determine the extent of these zones in the local sphere, in which these nycthemeral temporal data are obligatorily taken into account in the position calculations, then and only then can we give them uniform extents of 10° if the we have chosen this limit.

From this point of view for example and under the same terrestrial latitude of 45°, a planet rising at 0° Aries (therefore close to AS) must be included, to be classified as angular, in an orb of an extent more than double that which it would have if it were at 0° Libra. Aries is indeed one of the Short Ascent Signs (from 0° Capricorn to 0° Cancer) and Libra of those of long climb (from 0° Cancer to 0° Capricorn). The shorter the ascending duration of a degree or of a Sign, the more the orbs of angularity counted in degrees of ecliptic must be enlarged, and the longer this duration, the more they must be diminished.

It follows that the easiest way to determine these angularity orbs is to calculate them in the local sphere. This also makes it possible to integrate the parameter of the ecliptic latitudes in these calculations, which allows realistically assess planetary positions if the local sphere has been housed according to the Placidian system, which is based on the durations of daytime and nighttime arcs in 24 hours and is therefore the most consistent for this purpose. The ecliptic latitudes are then in this frame of reference a determining factor for realistically position the planets in the Houses. If the latitude of a planet is zero (it is then exactly on the ecliptic), this does not change its position. If its northern latitude is significant, it is then higher on the horizon than it appears to be in the ecliptic projection which is that of the classic Chart, and therefore higher in the House where it is located where it seems to be. And it is the opposite if its southern latitude is important.

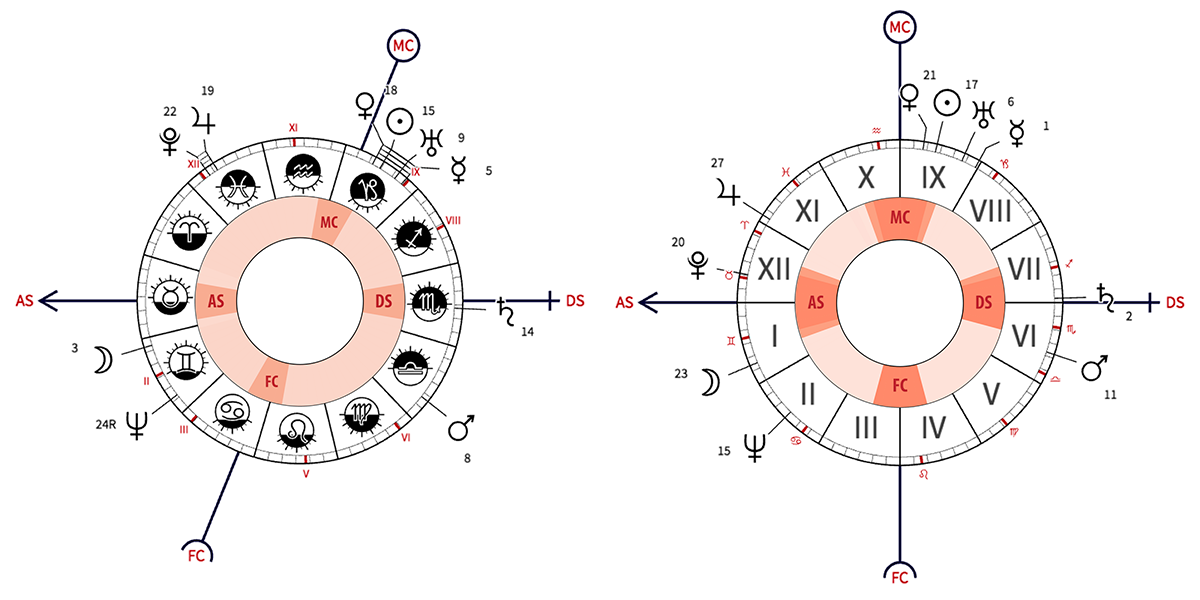

The charts of the sky below illustrate Choisnard’s error in his definition of orbs of angularity. In the left one (Ecliptic chart), they are based on the degrees of ecliptic longitude planets: this is the solution he has chosen. In the one on the right (House chart), they merge both longitudes and latitudes, do not measure than in the local sphere and are more extensive than those of Choisnard.

In summary, Choisnard was right, like all astrologers before him, to calculate the Aspects in degrees of ecliptic longitude in this reference frame of coordinates of the celestial sphere. But he was wrong in determining his orbs of angularity with the same degrees without taking into account the fact that in 24 hours in the local sphere, all these degrees are not traversed in the same durations. And he was also mistaken in not taking into account the ecliptic latitudes, not to calculate the Aspects, but to calculate as precisely as possible the planetary positions in the local sphere, therefore in their positions in Houses and their positive or negative heights on the horizon.

Moreover, the results of the Gauquelin statistics concerning the orbs of angularities, once checked and amended by the observations drawn from the experience and practice of real competent astrologers, show that the 10° orb before and after the AS-MC-DS-IC Angles is too narrow. It seems that it would be better to admit a much wider orb, of about 20° before and after the AS and the MC and above the DS, and an orb of 15° below the DS and on both sides. else from IC. In any case, it is on this experimental basis that the angularity orbs of our software are currently defined Astrosoft.

The Charts above illustrate the areas of angularity defined by default in our software Astrosoft. The chart on the left is now familiar to you: it is Choisnard’s Natal Chart, whose Ascendant is at 28° Libra. The one on the right was calculated for the same day and at the same place, but not at the same time. The Ascendant is this time at 28° Aries. The orange color delimits the zones of planetary angularity reported on the ecliptic, and the planets in gray designate the non-angular planets. Note that for the chart on the left, the zone around the AS Libra is very small: it covers about 32°. This orb of angularity is a consequence of the fact that Libra is one of the slowest rising Signs when rising.

For the Left Chart, the area around AS Aries is very large: it covers about 64°. This orb of angularity is a consequence of Aries being one of the fastest rising Signs when rising. In this case, Neptune in House XII which seems very far from the AS (about 17°) is actually very close to it (about 6°), and Pluto which seems close to the AS (about 15°) and in the center of House I is actually about 1° from House II, so much lower below the horizon, effect of its important ecliptic latitude South. This is the reason why it is displayed in grey: its location in the orange valuation zone around the AS and calculated in ecliptic longitude is only an illusion.

Through his graphic innovations, his contribution to the definition of the orbs of Aspects and Angularities and the rationality of his approach, Paul Choisnard greatly contributed to advancing astrology on these two points at the beginning of the 20th century. But he failed to understand that the ecliptic latitudes, whose role is so determining in the positioning of the planets in the local sphere, asked for the creation of another model of representation of the Chart which would have been usefully complementary to the one it is, and it is fortunate, managed to impose. The ecliptic latitudes therefore continued after him to be a repressed, even a stumbling block of astrology.

Choisnard, shaped by a naive scientism and a belief in the omnipotence of pure technique, wanted to make astrology a scientific knowledge. In his book The Astral Language, he lamented that this language had “unfortunately been distorted by most popularizers, almost totally ignoring astronomy which is the basis, and the scientific method which is its guarantee.” In another book, astrology and logic, he rightly opposed two different approaches to astrology: “While the scientific school holds astrology to be a science constructed by man with his current means, and therefore re-constructable by him thanks to a similar effort, the occultist school considers, on the contrary, that it has been bequeathed to man by beings more powerful than himself, products of an earlier and superior evolution, capable, in a word, of clairvoyance and of exploring to its limits the invisible and visible solar system.” He was right to criticize the irrationalist approach to this knowledge in this way, but he himself was not always rational in his approach, far from it.

To achieve his ends, that is to say, to make astrology a science in its own right, he would first have had to, after an uncompromising inventory, profoundly reform what could be in the archaic body of doctrine upon which traditional astrology is built. But he didn’t, while this corpus at least twenty centuries old is incompatible with the criteria on which modern scientificity is based. In other words, it never occurred to him to rethink, to radically re-theorize astrology and, like a Kepler, to rid it, for example, of its 4 Elements and its Planetary rulerships. He did not question this heritage, he accepted it as raw material on which he could exercise his talents as an engineer and an artilleryman, that is to say, a pure technician.

And even as a technician, not only was he not rigorous in his statistics, but he also believed, for example, that they could experimentally validate the fact that geniuses were born more frequently than others with a dominant zodiacal sign. of Air (Gemini-Libra-Aquarius). His did indeed… but he had consciously or unconsciously biased them to arrive at this result which subsequent, more rigorously conducted statistics have totally invalidated. If he had rethought, radically re-theorized astrology, he would never have ventured to statistically test such a hypothesis, given that not only is the doctrine of the 4 Elements actually foreign to astrology, but also that it has no kind of scientificity. Moreover, neither genius, nor imbecility, nor bullshit are listed in a Birth Chart.

To achieve his goal, it would have been necessary that in addition and above all before being this engineer-artilleryman-cartographer, he was also a thinker of astrology, which he never was. But as in the case of Kepler, this failure was nevertheless fruitful, since his work as an engineer and artilleryman-cartographer of astrology enabled it to progress in terms of the definition of the orbs of the Aspects and Angularities, as on that of the representation of Charts.

A solitary astrologer, marginal and misunderstood by his colleagues, not translated abroad and almost unknown to amateurs, Choisnard has not been educated, and his work is now unfairly forgotten. He is, however, the one who made astrology achieve one of its greatest advances at the beginning of the 20th century.

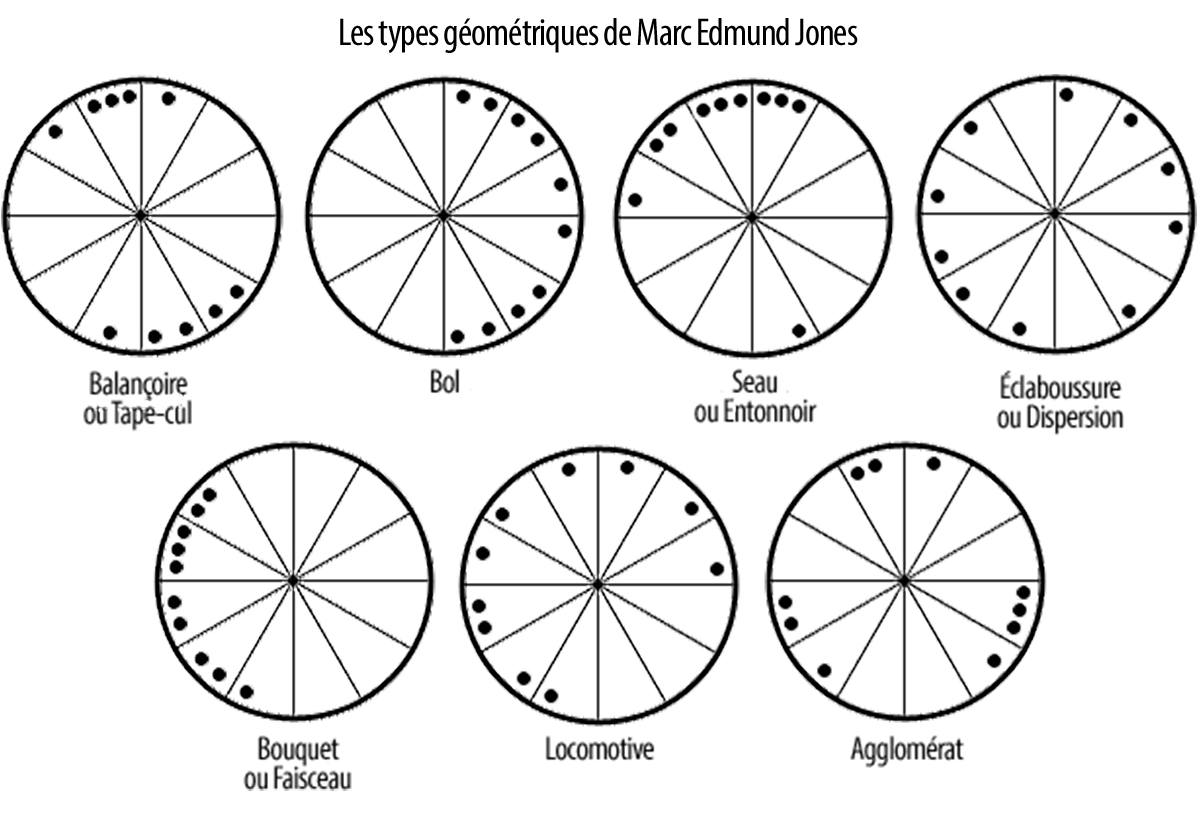

The “planetary drawings” by Jones are not Aspects according to their precise and contemporary definition. As such they should not be mentioned here. But after all the zodiacal angles of Ptolemy nor are they according to the same restrictive definition.

If Choisnard notably advanced the design of the Aspects and their orbs, the American astrologer and theosophist Marc-Edmund Jones (1888–1980) unquestionably made it regress. The character appalling of his negative contribution to this conception in particular and to astrology in general is so considerable that his work should not even be mentioned here.

Why do it then? Firstly because a setback or a regression are just as relevant to study as an advance and a progression, especially if they occur in the same period and concern the same field of knowledge. Then because Jones was the mentor of Dane Rudhyar, founder of the humanistic astrology, a school which has won a considerable number of followers all over the world and which consequently has widely propagated the aberrant conception of the Aspects of Jones. And finally because in this conception of the Aspects (or rather of the angular distances between planets or groups of planets), it is not the planets that these connect that matter, but the configuration itself of certain Aspect systems which can be interpreted, which can at the extreme limit completely do without planets, Signs and Houses. You could call it the “Kepler’s nightmare”.

It will not be a question here of technique, scholarly calculations, resolution of astronomical problems such as those posed by ecliptic latitudes (so we are a little off topic) and cartography. Marc-Edmund Jones did not have a training as an engineer and a military career as an artilleryman when he began his career as an astrological clerk like Choisnard: in his early days he was a prolific and successful author of short stories (short stories) and film scripts for Hollywood, including none left an unforgettable trace. It is not inevitable (after all, one can start as a screenwriter and become an excellent astrologer), but this first career strongly influenced, and in the worst possible way, his approach to the Aspects: this one is based on the only appearances, a spectacular staging and is therefore very cinematic. He contented himself with imagining 7 sequences of a pure fiction film based on simulacra of Aspect systems, to make them into actors to whom he gave striking names, and to script the whole thing.

The illustration below represents the 7 planetary drawings (“Jones patterns”) basic. It’s not really about Aspect systems, in the sense that these are based graphically on the geometric figures produced by certain particular configurations of Aspects. It is rather a general distribution (between concentration and dispersion) of the planets in 12 sectors which can be either Signs or Houses. Of course, genuine Aspects can fit within these systems, but that’s not the point.

The very hypothetical influences of these geometric shapes, with eclectic and grotesque names, can be interpreted as such, that is to say independently of the Planets, Aspects, Signs & Houses that they unite, in other words in a sidereal and staggering void. And many are the astrologers (in particular “humanists”) who do not hesitate, believing in the magic power of these images, which is simply insane. Note that some followers have found that this system is limited to 7 types (which correspond, hold on tight, to as many psychological types) was too limiting and therefore came up with other designs based on other distributions. It is true that the process lends itself to very many variations on the same Themes.

This system would have the fundamental quality, according to Alexander Ruperti, of encouraging the beginner to “look at the topic globally”, without getting lost in the complexity of the zodiaco-planetary configurations in the local sphere. With Jones’ drawings, indeed, the gaze replaces the analysis. By watching a Chart as one watches a film, one “sees” immediately that we are dealing with a guy “Tap ass” or “Locomotive” and one can immediately, without any intellectual fatigue, draw conclusions and a stratospheric interpretation. Which after all is not so serious when it comes to astrology a Jones system aficionado is able to write that “Each manifestation of life has a form which gives it its essential character (spiritual) and a determinable meaning according to the way in which it relates as a whole to universal life” (Dane Rudhyar, L’astrologie de la personnalité).

It was during the 1970s–80s that the “planetary drawings” of Jones have gradually established themselves as a new interpretation technique among astrologers participating directly or indirectly in the movement of “humanist” astrology which was then booming. Among the more temperate, their interpretation is superimposed on that of the Aspects to which it provides a general framework. At the holists the most simplifying ones, it can replace it.

One of the characteristics of “planetary drawings” is to be able to be applied indifferently to the celestial sphere or at the local sphere. In the first case, it applies to the distribution of the planets on the ecliptic and in the second to that in the Houses. As long as we stick to the classic representation of the Chart, the drawings are identical in both cases, since it favors the plane of the ecliptic. But if we apply the “planetary drawings” At House chart, we can have big surprises. Indeed, planets apparently relatively far from each other on the ecliptic (therefore quite scattered) can be very close (therefore very concentrated) if we refer to their real positions in the Houses, which can swing from a “geometric type” to another. But fortunately for them, most users of “Jones patterns” ignore these subtleties of astronomical reality.

To conclude, note that the study of the hypothetical effects of the concentration or dispersion of the planets on the ecliptic and/or in the local sphere is not called into question here. It can be a legitimate object of study. What is objectionable, however, is the frightening, delirious, fetishist and irrational static geometric-interpretative reductionism on which Jones’s system leads.

The “planetary drawings” are often confused with “Composed aspects” or put in the same category, when they are two different notions. While the former only apply to the distribution of planetary angles in general (from extreme concentration to maximum dispersion), the latter are interested in Aspect systems, therefore at specific and particular planetary angles. “Planetary designs” and “Composed aspects” are alike only insofar as they are the subject of a interpretation in itself, independent of the planets they bring together.

The concept of “aspect system” being more precise than the notion of “Composed aspects”, it is he who will be used here. It is defined as the set of Aspects that can form at least three planets between them (eg an opposition, a trine and a sextile). In the same Chart, a system of Aspects can be either independent (none of the planets it unites then forms an Aspect with another system), either attached to (at least one of its planets is in Aspect with another system). Several Aspect systems can thus be combined and superimposed in a complex configuration.

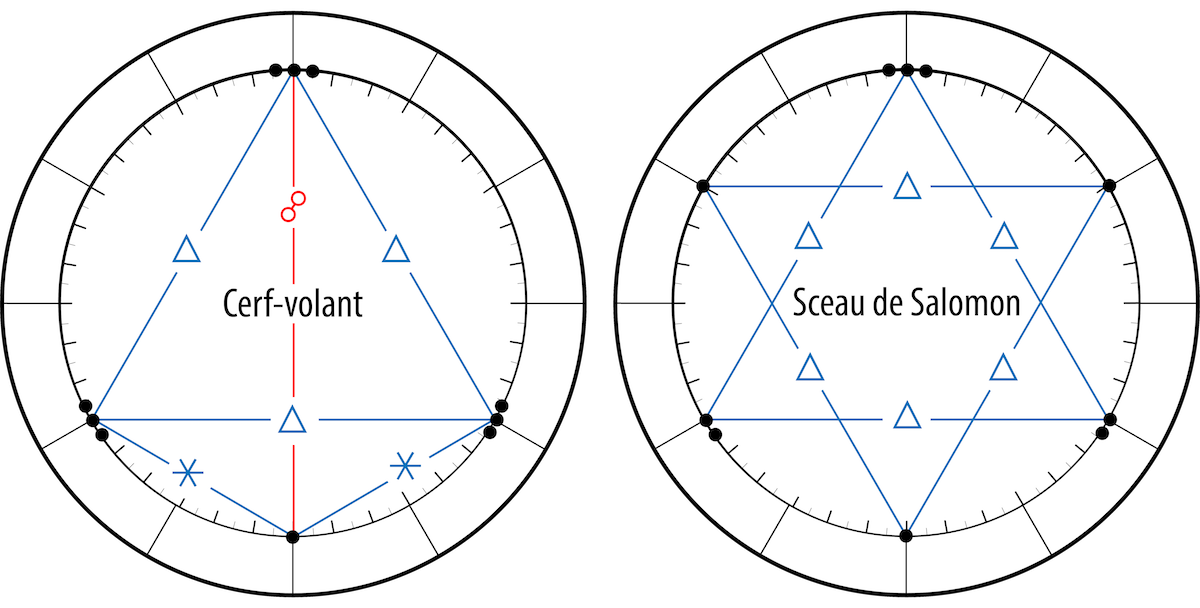

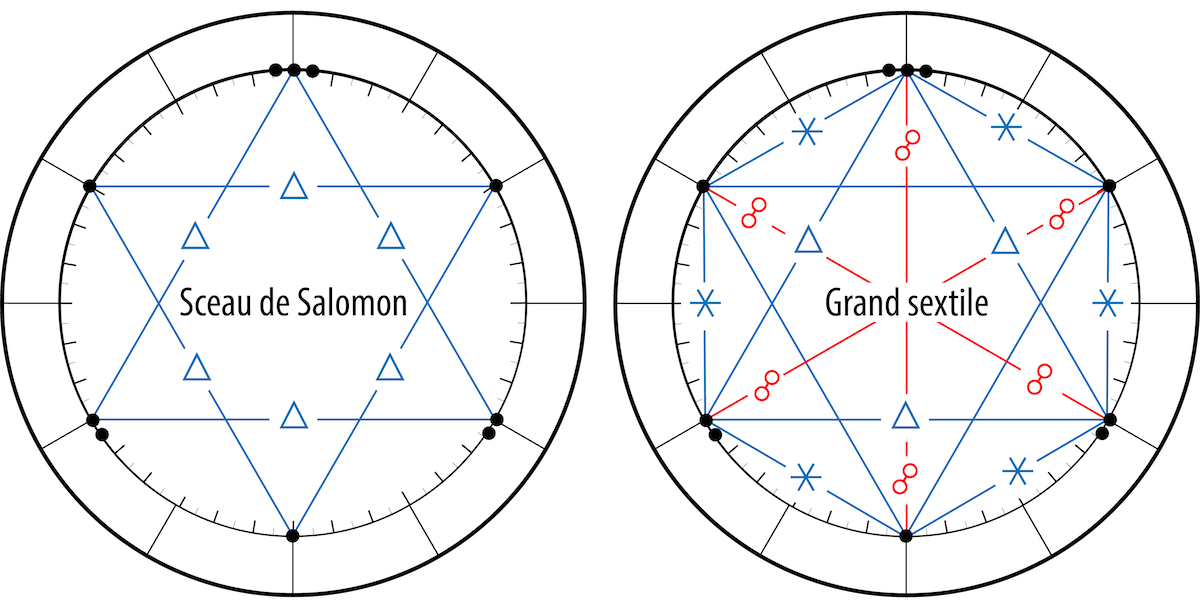

The systematic enumeration, nomenclature, naming and interpretation of Aspect systems are 20th century innovations. Their number varies according to the authors and according to whether or not the Minor Aspects are included. The most remarkable are those which unite all the planets in one single perfect geometric figure composed of major Aspects without orbs. As these scenarios are hyper-rare or even non-existent on the scale of astronomical frequencies, orbs are allowed, if possible not too large.

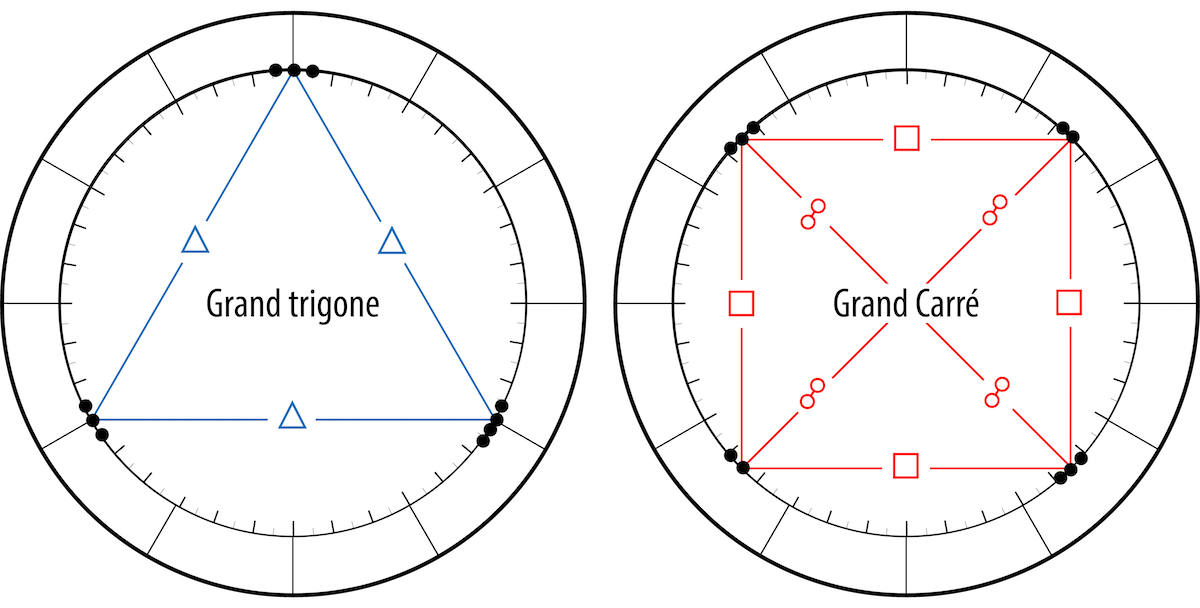

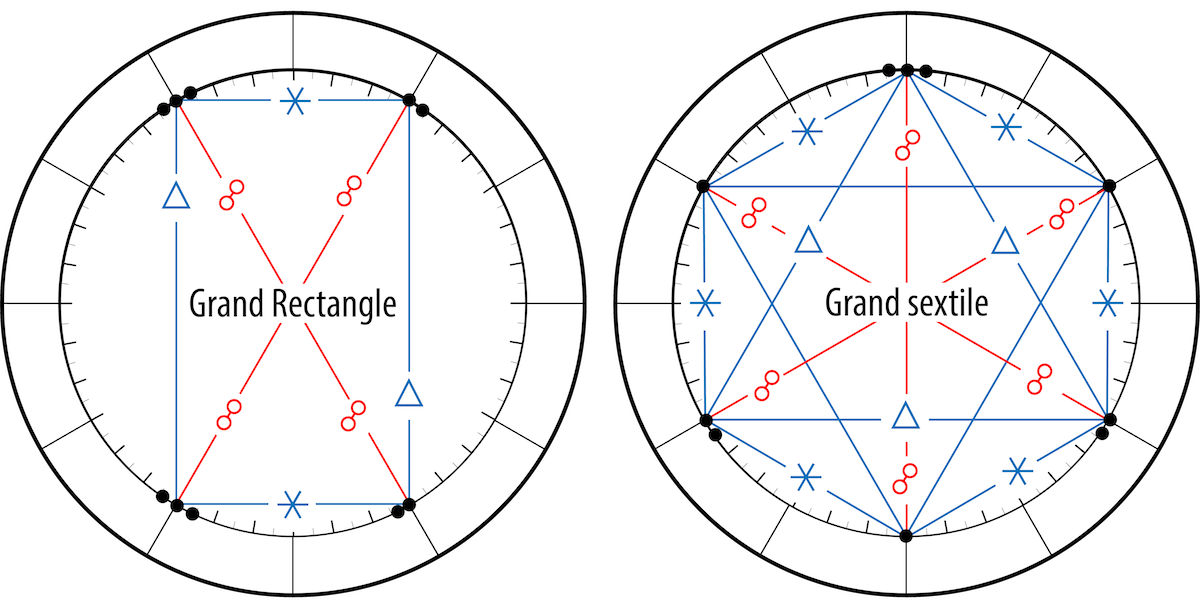

The rarest Integral Aspect system (it’s simple, you’ll never see one) is the “stellium”, planetary cluster composed of a conjunction of all the planets in a very restricted orb. The others are also extremely rare, but can occur on the scale of cosmic times. It’s about “great trine”, of “great square”, of “great sextile” and of the “great rectangle”. They can only be found in many Charts in their non-integral versions: they are then not made up of all the planets, but of a variable number of them. It only takes two or three planets that are not there to spoil this beautiful geometry.

The “great trine” and the “great square” are represented by the graphs below. Integral (this is the case in these figures) or not, these are the simplest systems. The “great trine” is indeed only composed of consonant conjunctions between them since connected by trines, and the “great square” of dissonant conjunctions by the squares and oppositions that connect them. For the most fatalistic astrologers, the “great trine” is hyper-beneficial and the “great square” hyper-evil. No comment. For the less deterministic, the hyper-benefits of “great trine” risk being squandered by a tendency towards ease and relaxation, and the hyper-curses attributed to “great square” conjured up by dint of vigilance and creative tension.

The “great rectangle” and the “great sextile” are represented by the graphs below. Integral (this is the case in these figures) or not, these are more complex systems, since they combine consonant and dissonant Aspects. For the most fatalistic astrologers, these are nightmares: benefits and evil spells are inextricably linked. For the less deterministic, several conditional answers are possible and the most frequent are the compensation and alternation balanced or not. In the best case, that of the balanced compensation, the effects of consonances-facilities balance and correct those of dissonances-difficulties and vice versa. In the worst case, that of unbalanced alternation, the relaxations of ease lead to the worst difficulties from which one seeks to escape by abandoning oneself to facilities in a vicious circle. Of course, all sorts of solutions can exist between these two extremes.

Among the other systems of Integral Aspects, the “kite” and the “seal of Solomon” or “David’s star” hold a special place. The “kite” (so named because of its shape) combines a maximum of consonant Aspects (sextiles & trines) and apparently a single dissonant Aspect (its central opposition). Apparently only, since the conjunctions connected by this opposition are thus partly consonant. For fatalists, who generally believe that the conjunction can only be consonant (which is an error), the evil spells of this unique opposition are warded off by the benefits of sextiles, trines and conjunctions, which can even take advantage of them. For the less deterministic, the same opposition, minority dissonance, creates a climate of tension preventing consonances from falling into relaxation and ease, etc.

As to “seal of Solomon” or “David’s star” (six-pointed star), it is only ever a lighter version of the “great sextile” to which we have kept its two great trines but which we have rid of its three oppositions. He therefore has no than a symbolic existence, and would therefore represent a perfect harmony example of tensions (of oppositions), in the genre of the great calm before the inevitable unleashing of a hurricane.

Integral or not, the systems of Aspects (apart from the “seal of Solomon”) have a real existence and deserve to be identified and studied as such (especially if they are partial, which is the most frequent case). But just read the interpretations that are generally given to realize the perplexity in which are plunged those who try to do so by overlooking and fetishizing those of the Aspects they unite. This fetishization of Aspect systems then produces the same throughs as that of the planetary drawings of Jones.

▶ Aspects theory and practice

▶ Les aspects, phases d’un cycle

▶ Aspects : existe-t-il un modèle traditionnel ?

▶ Aspects : théorie et bilan conditionaliste

▶ Introduction à l’interprétation des aspects

▶ The planetary Aspects and their orbs

▶ Les Aspects kepleriens

▶ Les “aspects” aux Angles

▶ Chronologie des Aspects et Transits

▶ Les Aspects planétaires

Les significations planétaires

par

620 pages. Illustrations en couleur.

La décision de ne traiter dans ce livre que des significations planétaires ne repose pas sur une sous-estimation du rôle des Signes du zodiaque et des Maisons. Le traditionnel trio Planètes-Zodiaque-Maisons est en effet l’expression d’une structure qui classe ces trois plans selon leur ordre de préséance et dans ce triptyque hiérarchisé, les Planètes occupent le premier rang.

La première partie de ce livre rassemble donc, sous une forme abondamment illustrée de schémas pédagogiques et tableaux explicatifs, une édition originale revue, augmentée et actualisée des textes consacrés aux significations planétaires telles qu’elles ont été définies par l’astrologie conditionaliste et une présentation détaillée des méthodes de hiérarchisation planétaire et d’interprétation accompagnées de nombreux exemples concrets illustrés par des Thèmes de célébrités.

La deuxième partie est consacrée, d’une part à une présentation critique des fondements traditionnels des significations planétaires, d’autre part à une présentation des rapports entre signaux et symboles, astrologie et psychologie. Enfin, la troisième partie présente brièvement les racines astrométriques des significations planétaires… et propose une voie de sortie de l’astrologie pour accéder à une plus vaste dimension noologique et spirituelle qui la prolonge et la contient.

Téléchargez-le dès maintenant dans notre boutique

Pluton planète naine : une erreur géante

par

117 pages. Illustrations en couleur.

Pluton ne fait plus partie des planètes majeures de notre système solaire : telle est la décision prise par une infime minorité d’astronomes lors de l’Assemblée Générale de l’Union Astronomique Internationale qui s’est tenue à Prague en août 2006. Elle est reléguée au rang de “planète naine”, au même titre que les nombreux astres découverts au-delà de son orbite.

Ce livre récapitule et analyse en détail le pourquoi et le comment de cette incroyable et irrationnelle décision contestée par de très nombreux astronomes de premier plan. Quelles sont les effets de cette “nanification” de Pluton sur son statut astrologique ? Faut-il remettre en question son influence et ses significations astro-psychologiques qui semblaient avérées depuis sa découverte en 1930 ? Les “plutoniens” ont-ils cessé d’exister depuis cette décision charlatanesque ? Ce livre pose également le problème des astres transplutoniens nouvellement découverts. Quel statut astrologique et quelles influences et significations précises leur accorder ?

Enfin, cet ouvrage propose une vision unitaire du système solaire qui démontre, chiffes et arguments rationnels à l’appui, que Pluton en est toujours un élément essentiel, ce qui est loin d’être le cas pour les autres astres au-delà de son orbite. Après avoir lu ce livre, vous saurez quoi répondre à ceux qui pensent avoir trouvé, avec l’exclusion de Pluton du cortège planétaire traditionnel, un nouvel argument contre l’astrologie !

Téléchargez-le dès maintenant dans notre boutique